Barely two months before India suffered its worst air crash in almost three decades, the country launched its first-ever lab for analysing “black boxes”, the flight data and cockpit voice recorders crucial to investigating aviation accidents.

The facility was a testament to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s campaign to upgrade air travel with a massive expansion of airports, airlines and infrastructure that has made India the world’s third-largest aviation market.

“Only through effective and independent investigations can future accidents be prevented,” aviation minister Ram Mohan Naidu Kinjarapu said when he inaugurated the facility in New Delhi on April 9.

On June 12, a London-bound Air India Boeing 787-8 Dreamliner crashed shortly after take-off in Ahmedabad, killing all but one of the 242 people on board and at least 29 on the ground.

India’s air safety, as well as the Tata-owned airline, are now in the global spotlight, as domestic and US and UK investigations, assisted by Boeing and engine-maker GE Aerospace, try to unravel what went wrong on Air India Flight 171.

But the Indian investigation team is considering sending the black box, which was heavily damaged, to the US National Transportation Safety Board, according to two people familiar with the matter.

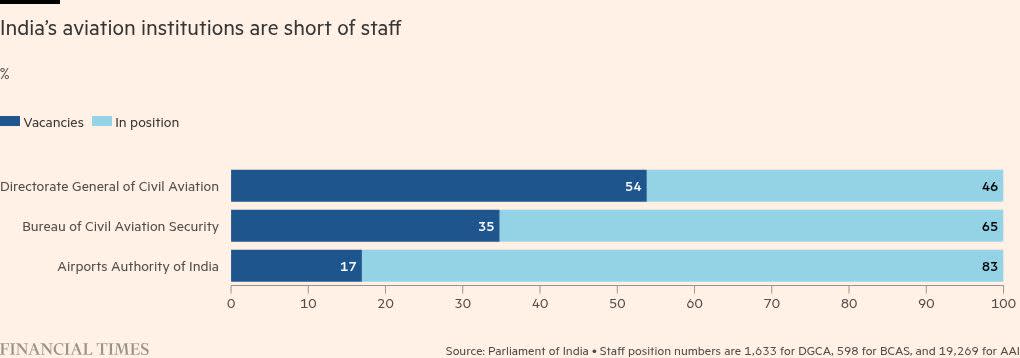

Analysts said the deliberations over the black box suggest a gap between India’s civil aviation sector ambitions and its institutional capacity. They also questioned the effectiveness of the industry’s lead regulator, the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), amid one of the world’s fastest expansions of air travel.

A parliamentary committee examining the aviation ministry said in March that more than half of the 1,633 staff positions in the DGCA were vacant, “raising fundamental concerns about aviation safety standards’ effectiveness”.

Analysts have described the directorate, which is an “attached office” of the civil aviation ministry, as highly bureaucratic and lacking in independence.

“The DGCA is clearly a weak link at the moment,” said Jitender Bhargava, author of The Descent of Air India and a former Air India executive director. “It hasn’t got corporatised or professionalised management like in countries abroad.”

The DGCA did not respond to a request for comment.

The breakneck expansion of India’s aviation industry — and the resuscitation of former state carrier Air India, which Tata bought in 2022 — has been part of Modi’s narrative of the country’s rise under his decade in power.

India Business Briefing

The Indian professional’s must-read on business and policy in the world’s fastest-growing big economy. Sign up for the newsletter here

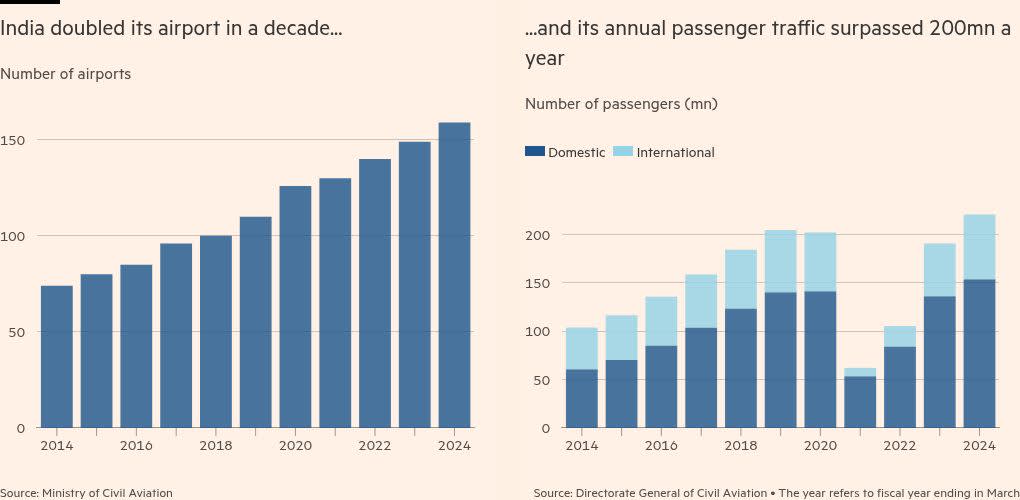

Ministers with Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata party this month celebrated the increase in the number of airports in India to 159 in 2025, up from 74 in 2014.

The prime minister has set a goal of 350-400 airports by 2047, the centenary of independence and his target year for making India a developed economy.

Mumbai is set to get a new international airport this year, built by the Adani conglomerate, as will New Delhi in its satellite city Noida.

“India is extremely ambitious about becoming a global airline hub,” said Vinayak Chatterjee, co-founder of the Infra Vision Foundation, an infrastructure-focused think-tank. “There has been a huge mobilisation of capital to build airports in the country.”

Air India and IndiGo, the country’s de facto airline duopoly, have bolstered this effort with bumper purchases of new aircraft, ordering 470 and 500 planes respectively in 2023, in what were both record deals globally.

Part of the push is also aimed at expanding access to more of India’s population. The government’s signature programme to subsidise air connections across the subcontinent is called Ude Desh Ka Aam Nagrik, or “let the common man fly”, and Modi has cited “people in rubber slippers” as the kind of aspiring Indians who should be able to afford to travel by air.

Many have taken him up on that promise: passenger traffic has more than doubled to 174mn last year from 83mn in 2014. But even before the crash, lawmakers and analysts had warned that oversight of the sector was not keeping pace with its expansion.

“The rapid expansion of aviation infrastructure . . . necessitates proportional growth in security capabilities and accident investigation references,” the parliamentary committee report said in March.

The committee noted that the government had slashed the budget for capital spending on civil aviation to $8mn this fiscal year, down from $87mn in 2023-4. “Such a steep decline may impact the aviation sector’s capacity for growth, modernisation and global competitiveness,” it warned. “Allocations are increasingly concentrated in select areas, while other critical aviation functions receive marginal funding.”

In a report published last month, Moody’s-affiliated rating agency ICRA said India’s aviation industry was facing “challenges” related to pilot and cabin crew availability that had resulted in “flight cancellations and delays”.

Since the Air India crash, the DGCA has chastised the airline several times for multiple lapses including crews working longer than maximum mandated hours.

Air India said in a statement it was “committed to ensuring that there is total adherence to safety protocols and standard practices”. It added that it had implemented orders from the directorate that called for the removal of certain personnel over the lapses.

Since the crash, scores of flights in India have been rescheduled or cancelled as airlines rush to undertake enhanced checks of their fleets.

In a statement on Tuesday, the DGCA did not name any airlines, but said that during “comprehensive surveillance” at major airports since June 19 it had found multiple cases where reported defects had “reappeared many times” on aircraft, indicating “ineffective monitoring and inadequate rectification action”.

Among several other issues with ground handling and aircraft maintenance it found that “defect reports generated by the aircraft system, were not found recorded in the technical logbook”.

Mohan Ranganathan, an air safety expert and former pilot who has worked with India’s government, said staff shortages across the sector had been a mounting problem over 20 years.

“The load factor has increased, but the shortage in manpower means mandatory work is not done,” he said. “Everything is swept under the carpet.”