Israel’s attacks on Iran threaten to cut China off from critical oil trading partners, highlighting its need for greater energy independence and disrupting Beijing’s hopes for a bigger role in the region.

For years, China has used its relationship with Iran to expand its influence in the Middle East, while making cheap Iranian crude, and Gulf supplies more broadly, a bedrock of the energy mix for the world’s biggest buyer of oil.

Chinese President Xi Jinping said this week that all parties to the conflict between Israel and Iran should work “as soon as possible to prevent further escalation of tensions”. China has said the US should not interfere with its “normal trade” with Iran and has opposed US-led sanctions.

“Of course, China is worried [by the latest attacks],” said Gedaliah Afterman, an expert on China and the Middle East at the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy and Foreign Relations in Israel.

“If this situation continues to escalate, then they lose quite a bit, both in terms of their energy security and Iran as a strategic card that China holds.”

Since US-led sanctions on Iran’s nuclear programme were stepped up in late 2018, Beijing and Tehran have strengthened ties.

Beijing has become Tehran’s most important economic lifeline, buying the vast majority of Iranian oil shipments and supplying the country with electronics, vehicles and machinery, and nuclear power equipment.

Last year, Iranian oil accounted for as much as 15 per cent of the crude shipped to the world’s second-biggest economy. Overall, China last year imported about 11.1mn barrels of oil a day, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

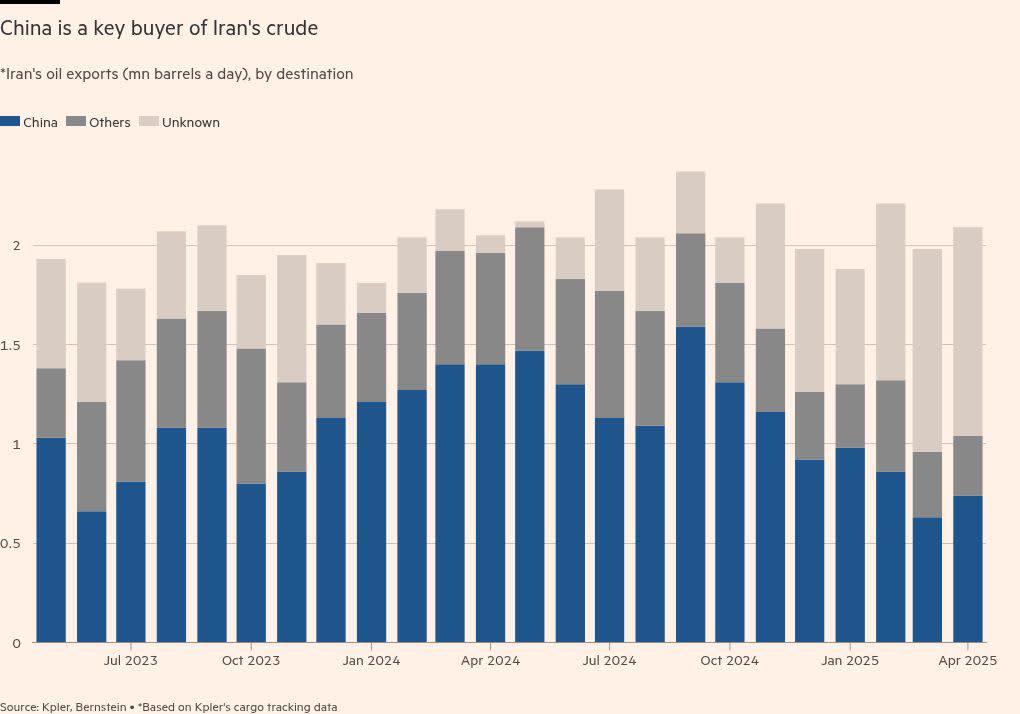

Chinese purchases of Iranian crude edged higher through most of 2023 and 2024 but started to ease late last year as the threat of new US sanctions increased, according to data from cargo tracking research group Kpler and Bernstein.

Iran exported 2.4mn barrels of crude a day in September 2024, with China accounting for 1.6mn barrels. By April, Iranian shipments had fallen to 2.1mn barrels a day, of which China accounted for 740,000 barrels. Malaysia is also an important exporter to China as cargoes shipped from Iran are relabelled or transferred to avoid sanctions, analysts said.

Analysts from Fitch Ratings this week said that, “even in the unlikely event that all Iranian exports are lost”, they could be replaced by spare capacity from Opec-plus producers.

Other, more severe, energy disruptions could emerge. The war, which is at risk of spilling over into a broader regional conflict, has already sparked threats from Iran that it could block the Strait of Hormuz.

Hundreds of billions of dollars in oil and gas are shipped through the waterway to China from nearby Gulf States each year, including Saudi Arabia, China’s biggest supplier of crude outside Russia.

China does not officially publish the volumes of its strategic petroleum reserves. But Michal Meidan, head of China research at the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, estimates that across all storage types there is around 90-100 days of cover in the event that flows into the country are restricted.

Beyond a growing reliance on Saudi oil, S&P Global analysts have noted that more than 25 per cent of China’s liquefied natural gas imports last year came from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. While China holds 15 LNG supply contracts with these two Gulf states, importers could be forced to purchase from the spot market at higher prices, S&P analysts said.

For China, the Israel-Iran crisis war comes amid a tectonic shift in the country’s energy mix. The country has for decades been the world’s biggest oil user. Under Xi, China is racing to boost its energy independence, a transition that ultimately requires a massive increase in renewable energy and the electrification of the country’s transport and manufacturing base.

A boom in solar and wind has taken renewables’ share of electricity power plant capacity to 56 per cent last year, up from around one-third a decade ago.

The “key takeaway” for Xi’s administration from the crisis, according to Neil Beveridge, head of Asia-Pacific research at Bernstein, will be to double down on its self-sufficiency drive.

“If it wasn’t happening fast enough before, it will be happening even faster now,” he said.

Analysts said China might benefit in the short term as Washington’s attention is more focused on the Middle East, rather than tensions with Beijing.

However, longer term a weakened Iran threatens to undermine China’s diplomatic influence in the region and potentially disrupts its desire to portray itself, at least domestically, as a credible mediator in global conflicts.

In 2021, Beijing signed a 25-year co-operation programme with Tehran. Iran also joined the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in 2023, part of China’s efforts to position itself as a responsible power and offer developing economies an alternative to US-led global institutions.

In 2023, Beijing touted its role mediating a Saudi-Iran deal and released a 12-point peace proposal for the Russia-Ukraine war.

Despite these moves, Beijing appears likely to remain on the sidelines in the Iran-Israel conflict, as was the case with the fall last year of ally Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, highlighting the limits of China’s foreign policy influence.

Jingdong Yuan, director of the China and Asia security programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, said that while China rhetorically supports countries “seen as receiving unfair treatment or coercion from the west”, in reality Beijing’s approach to regional conflicts was “always cautious”.

Beijing will be concerned about the impact on other allies in the region, such as Saudi Arabia. “The demise or the collapse of the Iranian system or the Iranian power as we knew it is not good news for China,” said Yun Sun, an expert on Chinese foreign policy with the Stimson Center, a US think-tank. “That indirectly means that American influence has expanded.”

Additional reporting by Wenjie Ding in Beijing