A $23bn sale of ports by CK Hutchison has raised concerns in the logistics industry that the deal could hurt competition and disadvantage rivals by making the world’s biggest shipping company the top operator of container terminals globally.

The deal to sell 80 per cent of the Hong Kong conglomerate’s global ports portfolio to a subsidiary of the Mediterranean Shipping Company would hand the Swiss-Italian shipping line control over a critical amount of the world’s port infrastructure, some industry analysts and executives fear.

The impact of the sale is “massive”, said one port industry executive, with the proposed MSC agreement raising “significant concerns” among rival shipping lines about their long-term access to port infrastructure.

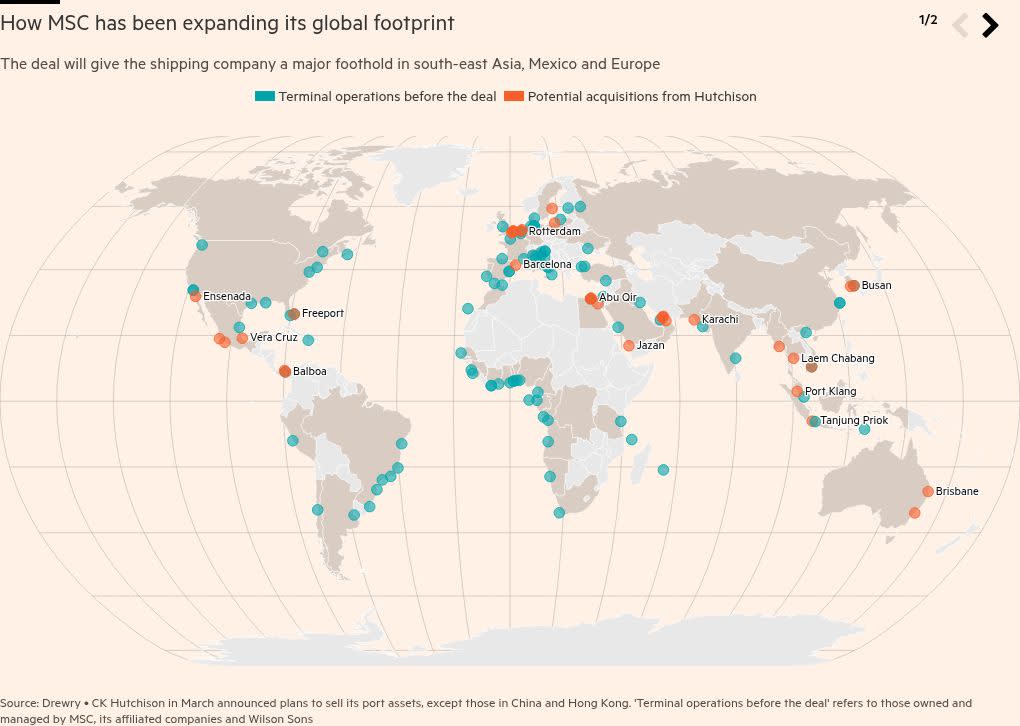

A consortium led by port operator Terminal Investment Limited — majority-owned by MSC — together with BlackRock’s infrastructure unit GIP in March agreed to buy stakes in 43 ports in 23 countries.

Hutchison struck the deal — which also includes the takeover of two Panamanian ports and already faces scrutiny by the Chinese government — following complaints from President Donald Trump that China was “running the Panama Canal”.

If approved by regulators, it will allow MSC — owned by the billionaire Aponte family — to leapfrog its main competitors in the ports business to become the world’s largest container terminal operator with a projected 8.3 per cent of global share, according to maritime consultancy Drewry.

“Considering [MSC’s] shipping business, this [deal could] potentially lead to reduced competition and higher barriers to entry for other players,” said Kun Cao at consultancy Reddal.

Another port sector executive said: “If you’re a shipping line and then your biggest competitor suddenly has all this [port] capacity, you’re naturally concerned because you don’t want to feed more revenue to your competitor, or risk that they’ll stop you coming or not give you the best berth windows.”

The person added that while shipping lines made 10 to 15 times more profit from shipping containers than the port terminals did from unloading them, the investment would allow them to “get rates higher, and squeeze capacity to make as much money as possible”.

The deal’s supporters noted that the Chinese owned a sizeable portion of global ports, with state-backed operators China’s Cosco and China Merchants holding a combined market share of more than 12 per cent.

They also pointed out that the deal would leave MSC with market share similar to its nearest rival, Singapore’s PSA International, which held 7.2 per cent in 2023.

However, analysts warned that the combination of being the largest shipping group and largest port operator potentially handed MSC a significant advantage over competitors.

The transaction will give MSC a major foothold in south-east Asia, Mexico — where Hutchison is the largest player with four terminals — and Europe, where Hutchison is the dominant operator in major ports including Rotterdam, according to Drewry.

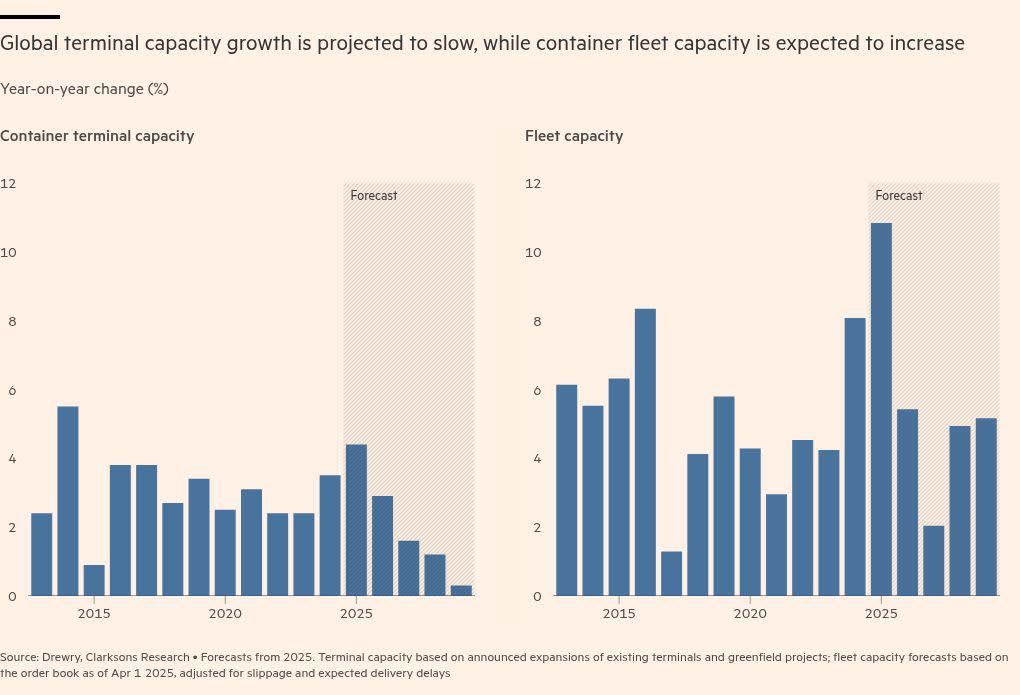

Concerns over the huge expansion of MSC’s portfolio comes at a time when ports in Asia and Europe are already facing congestion challenges, while orders for new ships are at record highs as shipping lines reinvest soaring post-pandemic profits.

Analysts warned that pressure would only grow on container terminals as new ships come on stream, increasing the value of MSC’s newfound dominance if the Hutchison sale is confirmed.

Eleanor Hadland, Drewry’s senior associate in ports and terminals, said capacity growth for the port sector was now “significantly lower” than two decades ago, even as additional container shipping capacity was set to increase.

Another shipping industry executive noted that the MSC-BlackRock deal was part of a much wider process of vertical integration in the industry, for example, with companies such as Maersk, whose APM Terminals business exceeded the size of its own shipping fleet.

Two people close to the deal dismissed concerns over MSC’s growing dominance of the market, noting that the deal contained legal commitments to continue operating the terminals “without discrimination” and on the same basis as today.

But the Chinese government’s critical stance since March over the deal has also cast a shadow.

While the deal does not include CK Hutchison’s 10 ports in mainland China and Hong Kong, Beijing has criticised the transaction, saying it would undermine “national interests” by giving the US the opportunity to curb China’s shipping and trade.

China’s antitrust regulator has said it would launch a review into the deal. The consortium has held talks with China’s antitrust regulator, as it seeks to ensure their approval, the Financial Times reported this week.

MSC declined to comment.

Lars Jensen, chief executive of consultancy Vespucci Maritime, said fears of MSC abusing its position were overblown. “There’s undoubtedly a valuable competitive advantage for MSC here. But this deal will allow them to optimise their shipping operations, and make more money from their ships, not treat their competitors worse.”

Robbert van Trooijen, founder of shipping and ports advisory Inception Partners and a former Maersk executive, said as competition for port access grew, smaller operators still feared they might find themselves squeezed.

Nevertheless, he pointed out that concerns over vertical integration of carriers developing large ports and logistics portfolios “could be a difficult case to argue with regulators”.

Rico Luman, a senior economist at ING focusing on transport and logistics, said: “In times of heavy congestion and capacity shortage, such terminals [could] prefer the home carrier.”

Reddal’s Cao said with its influence over port infrastructure, MSC could gain access to sensitive shipping data that could be used to its competitive advantage.

Antitrust regulators, including those overseeing Rotterdam’s Hutchinson-owned leading container terminal operator, are likely to “take a keen interest in the transaction” given its size and scale, added Drewry’s Hadland. This would potentially extending the time needed to complete the deal.

A person with knowledge of the deal confirmed that antitrust concerns over some terminals — including Rotterdam — were “on our radar screen”.

The consortium was prepared to drop some ports if they faced antitrust concerns, they added.

“We may have to give up a terminal [here or there] . . . [and] we are going to be prepared to do that.”

Additional reporting by Ivan Levingston and Arash Massoudi in London