Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A closely watched auction of 40-year Japanese government debt has drawn the lowest demand in 10 months as concerns mount over the world’s third-biggest bond market.

Demand for the government’s offer on Wednesday of about $3.5bn of 40-year notes attracted a bid-to-cover ratio — the number of bids received against securities offered — of 2.2, the lowest level since July 2024 and a reflection of what some traders have called a “buyers’ strike” among Japanese life insurers and other domestic participants.

UH-OH.

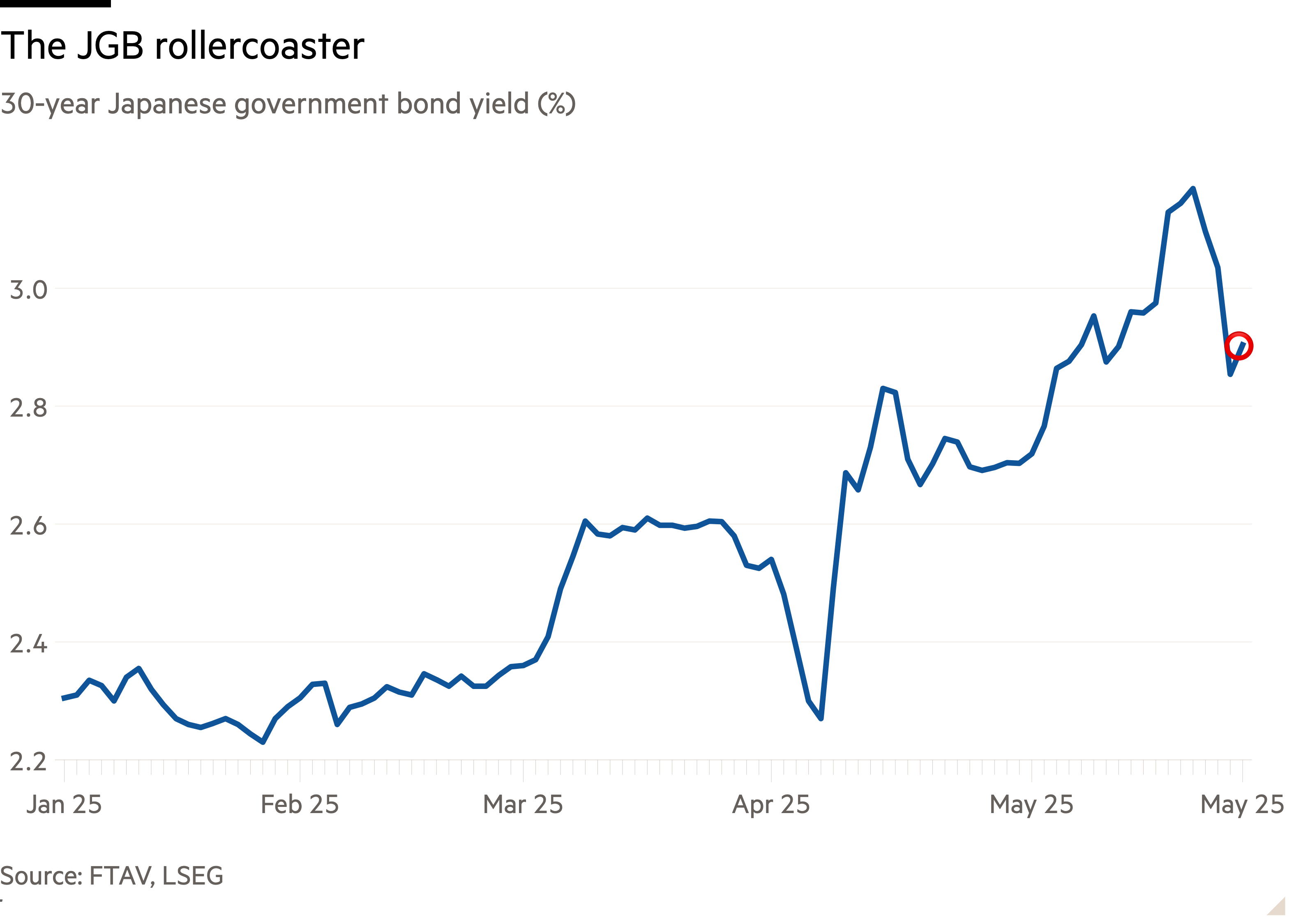

Longer-maturity Japanese government bonds had in recent days tiptoed away from the near-meltdown they suffered earlier this month, thanks to some jawboning from the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan, and hints that long bond supply could be pared down.

But today’s weak auction has reignited fears over investor appetite for JGBs. While yields remain far below the peak they touched last week, and today’s rise isn’t huge, the reversal is . . . suboptimal.

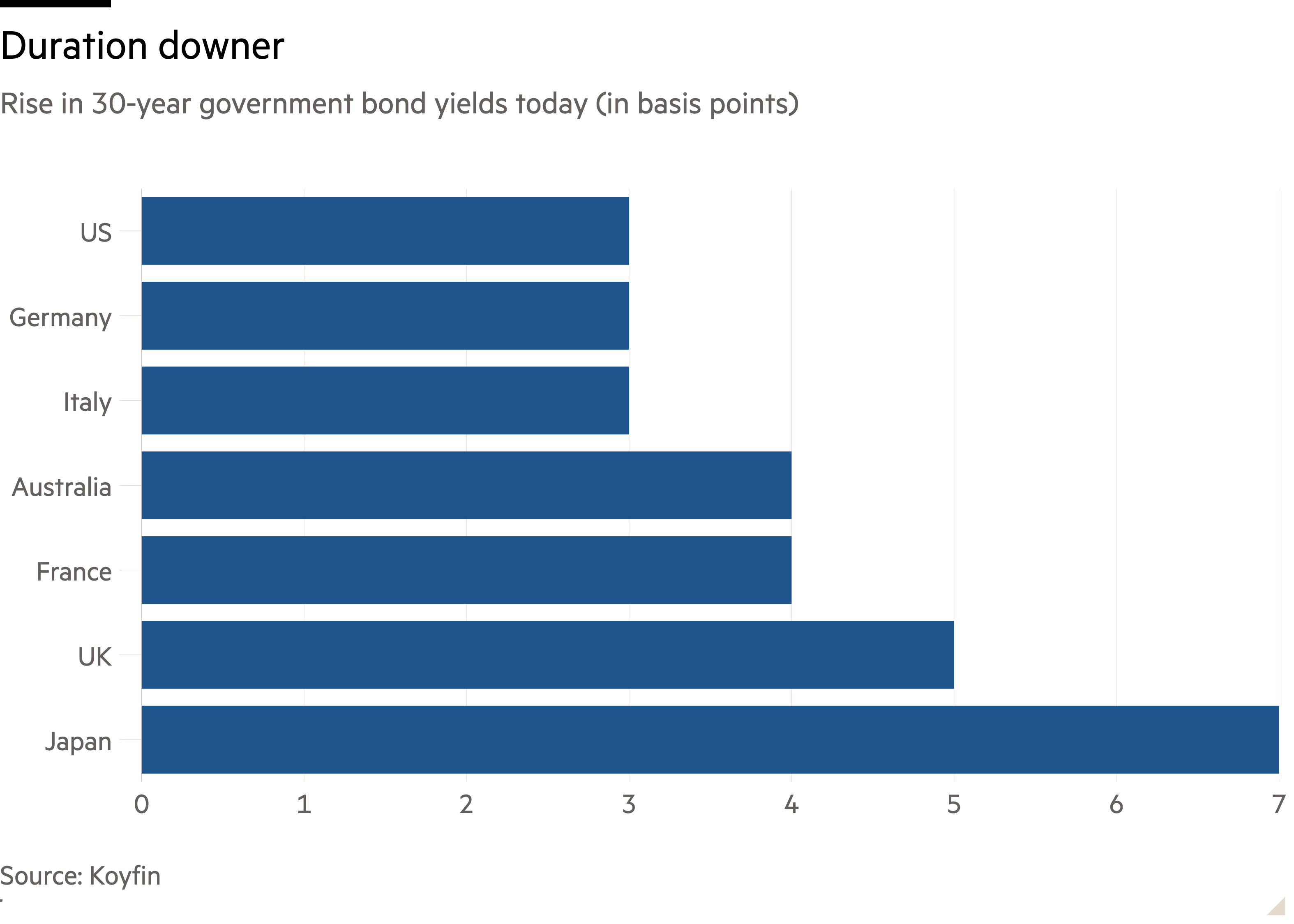

If this had been a Japan-only story then it might be easy to ignore, but the JGB sell-off was a major factor in the recent global duration wobble, and today’s renewed weakness seems to once again be infecting the long end of the yield curve pretty much everywhere.

The Japanese government bond market is one of the largest in the world, so it has always exerted some influence elsewhere. The Bank of Japan’s “yield curve control” programme certainly seems to have acted as an anchor for global bond yields for much of the past decade. But the way JGBs now seem to be actively driving other developed bond markets is interesting.

As Ajay Rajadhyaksha wrote on FTAV last week, the core problem is an acute imbalance between supply and demand. There just doesn’t seem to be enough investor appetite — locally or internationally — to digest the still-massive issuance.

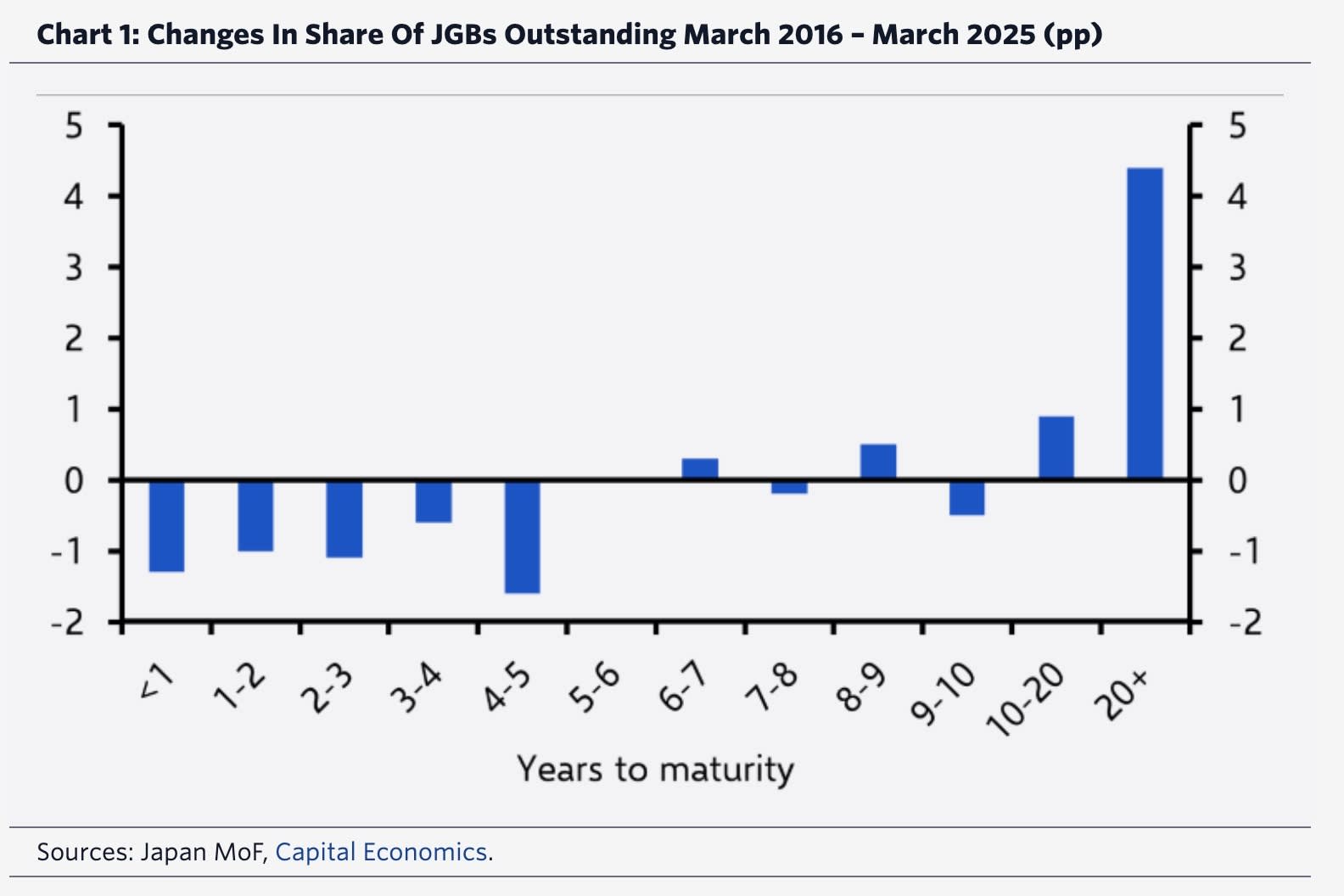

Japanese insurers have almost stopped buying long JGBs because of tweaked solvency ratios (and have been hosed by unrealised losses already); Japanese banks favour shorter-term JGBs (where yields are now positive); and the Bank of Japan is now paring back its QE programme. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Finance has been skewing issuance heavily towards the long end to lock in low borrowing costs for many years.

Thomas Mathews, head of Asia Pacific markets at Capital Economics, points out that the Japanese authorities still have a lot of levers they could pull, such as a shift in issuance strategy that the Ministry of Finance has already hinted at. The BoJ could also tweak the shape of its quantitative tightening programme, and reinvest more from its maturing bonds in the long end of the curve.

But it could still have consequences globally, given the massive troves of government bonds that Japanese financial institutions have accumulated over the past few decades to counteract the lack of yields at home, Mathews warns:

We’ve been sceptical of claims that Japanese investment is about to flood back home due to higher local yields. But that’s because we thought reduced short-term FX hedging costs (thanks to a relatively flatter JGB curve) would outweigh the effects of higher yields, making foreign bonds more attractive on a that basis. Indeed, we saw something like the reverse of this in 2022 when the US curve was flattening; despite higher yields abroad Japanese residents sold foreign bonds.

But if the JGB curve is steepening, e.g. due to fiscal/supply-demand concerns, then this argument holds less weight. Our sense is that, in this case, the large pool of Japanese investment abroad may have helped keep a lid on JGB yields, albeit at the potential expense of bonds elsewhere. After all, if Japanese investors were to sell foreign bonds at scale, it could push global term premia up further.

Tl;dr we may have to get used to JGBs exerting an unusual amount of influence over the global bond market.