Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

European defence companies say Japan has accelerated its opening to non-American suppliers of military equipment since the election of US President Donald Trump.

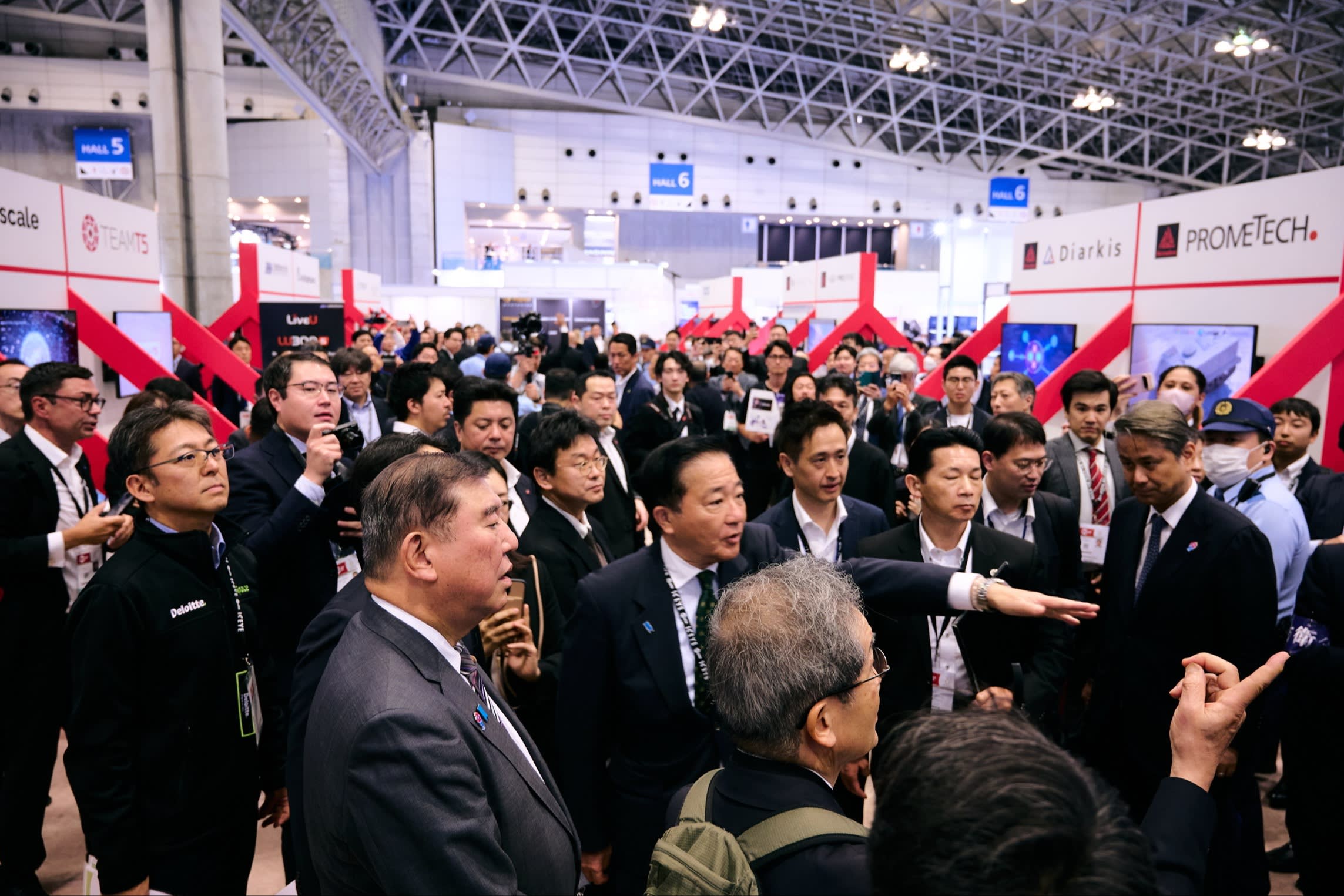

Tokyo’s increasing willingness to look beyond its traditional defence partner for procurement was the main focus of attention at Japan’s largest-ever defence sector trade show in Makuhari near Tokyo this month.

It comes after Trump has rattled US allies around the world by raising questions about Washington’s commitment to joint defence.

Company representatives at the three-day Defence and Security Equipment International event said Japanese politicians and officials had made clear they were now more open to deals with non-US contractors backed by plans to substantially increase national defence spending.

“In the past, it was dominated by the US,” said Lars Eriksson, country manager for Sweden’s Saab in Japan. “Rather recently, it has opened up for other countries to get a bigger share of the cake.”

“There’s a shift in Japan,” said Paul MacGregor, managing director of Roke, a British sensors and information defence group. He said the sentiment among Japanese officials was increasingly “we like something as long as it’s not American”.

Roke, which is owned by UK-listed Chemring, supplied electronic warfare systems to Japan’s Self-Defense Forces for the first time last year, and is hoping to earn £100mn in revenue in the Japan market over the next five years through an expanded relationship with local trading house Kaigai.

UK, Italian, Scandinavian, Israeli and German defence manufacturers echoed MacGregor’s ebullience, saying the domestic arms market had completely changed in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

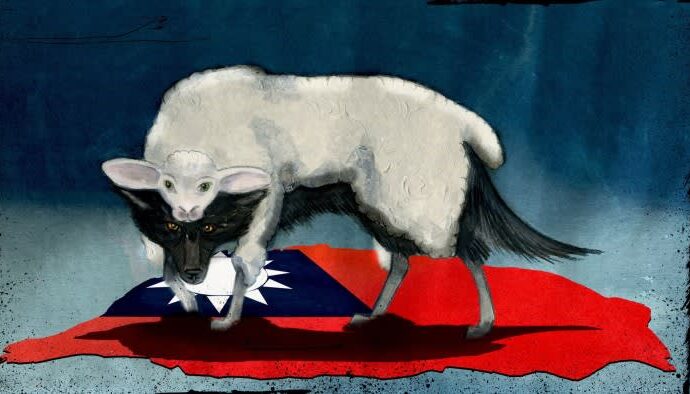

The invasion raised Tokyo’s awareness of geopolitical uncertainties and helped persuade policymakers to do more to counter what they see as the strategic challenge of an increasingly powerful and assertive China.

In 2023 Japan announced plans to raise its defence spending to 2 per cent of GDP by 2027, up from the self-imposed cap of about 1 per cent of GDP it had maintained since the 1960s.

In a sign of the shifting commercial landscape, 471 companies from 33 countries attended the DSEI trade show, up more than 60 per cent on the previous event in 2023. Of them, 128 came from Europe, the largest contingent ever.

“Japan feels much more receptive to UK, European and wider international allies’ offerings, in contrast to a hitherto much more US-centric approach,” said James de St John-Pryce, business director of British armoured vehicle manufacturer NMS UK.

“The mutual co-operation between the UK and Japan has become much more pertinent in the midst of mixed messaging from the US,” he said.

Robert Dane, chief executive of Ocius, an Australian marine drone supplier, said the “lightning pace” of his company’s talks on supplying Japan’s navy had confounded expectations since last October. “I was told it would take six years of drinking sake,” he said.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba underscored Japan’s growing openness to deeper partnerships with international manufacturers of missiles, drones and fighter jets in a speech at the trade show on Thursday.

“It’s critically important to promote co-operation in the transfer as well as joint development and production of defence equipment to ensure peace and stability of Japan and the wider region,” Ishiba said.

Japan’s joint development flagship is the Global Combat Air Programme, a multibillion-dollar fighter jet project with the UK and Italy that also has the explicit goal of finding cutting-edge alternatives to closely held US military tech.

“The essence of the GCAP programme has been freedom of action and freedom of modification for each of our nations,” said Andrew Howard, director of Future Combat Air at Leonardo UK, one of the four companies that will supply avionics to the fighter jet.

“The desire to retain significant sovereign capabilities in each of the three nations . . . is being reinforced by the concerns around the US behaviour,” he added.

The Trump administration has sought to ease concerns among Asia allies about its commitment to them. Visiting Japan in late March, US secretary of state Pete Hegseth praised Japan as a “model ally” and said Washington and Tokyo had begun setting up a “war-fighting” headquarters.

“America First does not mean America alone,” Hegseth said.

Participants at the defence trade show agreed that the US would remain Japan’s primary defence collaborator and supplier even if procurement and joint development with Europe grew substantially.