Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

South Korea’s interim leader has announced his resignation as he plans to stand for president in snap elections next month, throwing Asia’s fourth-largest economy into further uncertainty.

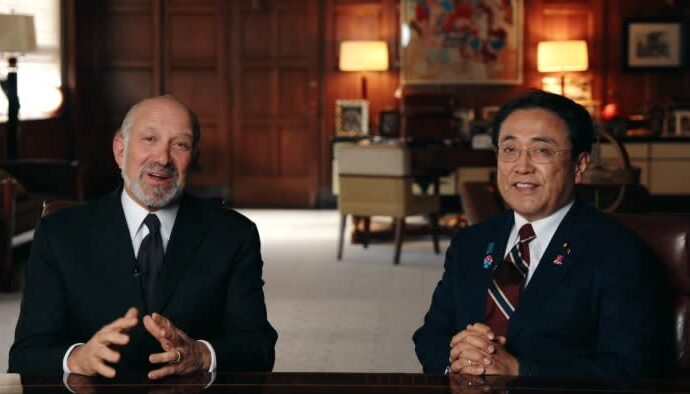

Han Duck-soo, a career technocrat who has never held elected office, took over as acting president after the impeachment in December of conservative president Yoon Suk Yeol over his failed attempt to impose martial law.

Han, who also serves as prime minister, had been expected to steer the fiercely divided country through to the presidential election on June 3.

He had also been overseeing trade talks with the US, following tariffs enacted by President Donald Trump that have hit South Korea’s export-oriented economy.

But Han is now preparing to stand for president himself, according to people familiar with his thinking.

Han told reporters on Thursday that rather than “completing the heavy responsibility that I handle now”, he was stepping down as acting president and prime minister in order to “take on an even heavier responsibility”. He is expected to launch his candidacy on Friday after his resignation takes effect at the end of Thursday.

His decision to step down comes amid growing fears among South Korean conservatives that none of the prospective candidates from Yoon’s People Power party appear capable of mounting a credible challenge to leftwing frontrunner Lee Jae-myung.

Lee was the preferred candidate of 48.5 per cent of respondents to a Realmeter survey released this week. The most popular PPP candidate garnered the support of 13.4 per cent of respondents. Han was not included in the poll.

“Even when Han announces his candidacy, this election will still very much be Lee’s to lose,” said Erik Mobrand, a political scientist at Seoul National University.

Han said on Thursday that South Korea “cannot protect our core interests with irrational, poll-driven economic strategies”, in a thinly veiled reference to Lee’s reputation among critics for economic populism.

“Unless we break free from political extremism and establish a framework for bipartisan co-operation, division and conflict will keep recurring — regardless of who takes power,” he added.

But analysts said the decision of Han, once widely regarded as a bipartisan figure, to leave his post and enter the political arena himself was likely to fuel political divisions.

Opposition politicians have accused Han of using trade negotiations with the US as a springboard for his presidential ambitions, while many on the South Korean left accuse him of playing a prominent role in Yoon’s doomed martial law gambit.

“Han will try to play the role of a unifier less tarnished by partisan associations,” said Mobrand. “But given everything that has happened since Yoon’s martial law declaration, this will be a real stretch.”

In a separate development on Thursday, the country’s supreme court overturned Lee’s recent acquittal on charges of violating electoral laws by “spreading falsehoods”.

While a final verdict is not expected before June’s presidential election, analysts said the ruling could still harm the campaign of Lee. He has past convictions for drink driving and impersonating a prosecutor and faces several other criminal proceedings including charges of illegally remitting funds to North Korea. Lee denies all wrongdoing.

The acting presidency will pass to finance minister Choi Sang-mok. Choi also served as interim leader for several months this year after Han was impeached by the leftwing-controlled parliament over his refusal to fill several spots on the country’s Constitutional Court.