Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

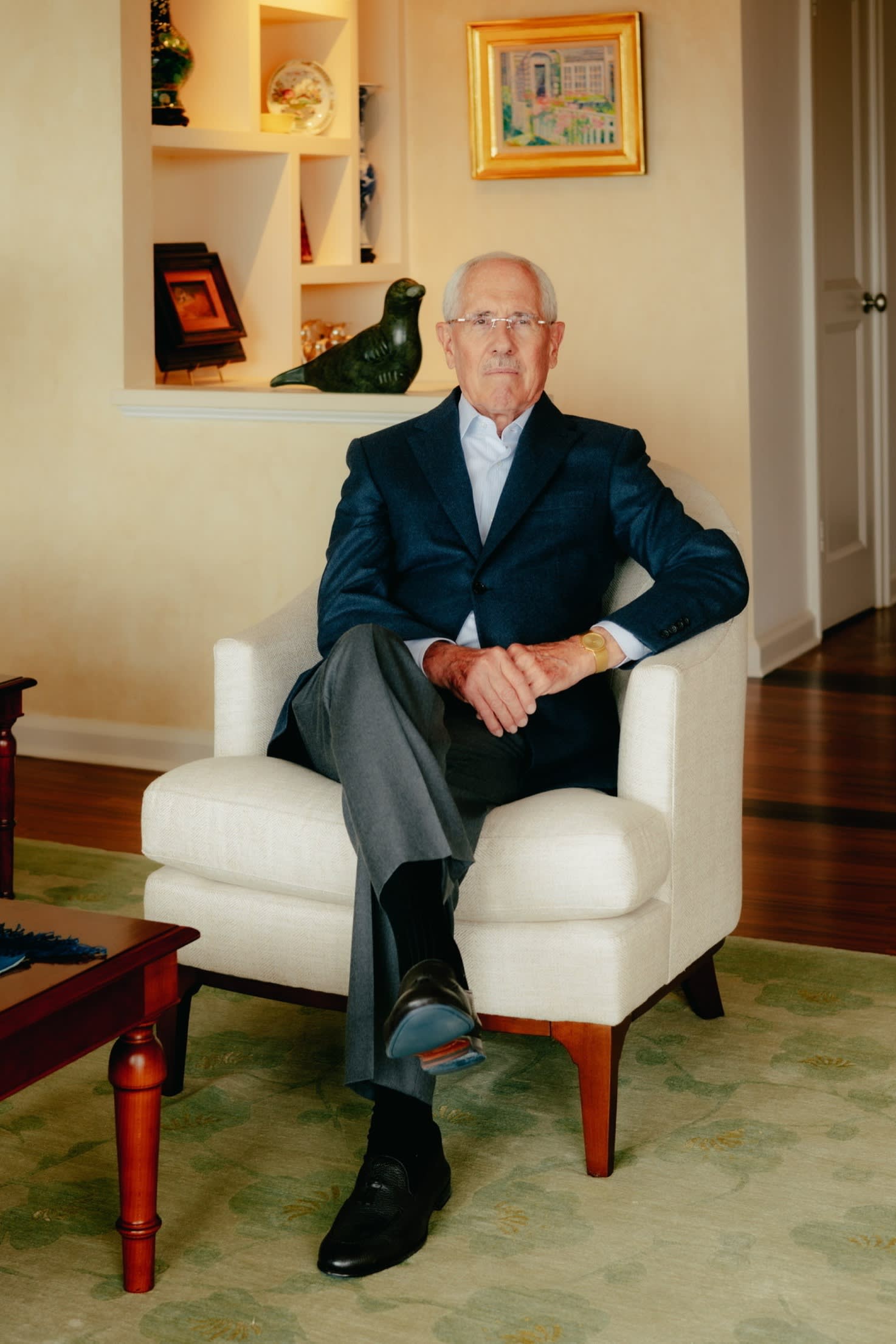

The American businessman Alan Medaugh, 81, has spent 50 years building up an unparalleled collection of woodblock prints by the famed Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). With 850 works, his collection is the largest in private hands outside Japan, and now Medaugh has donated 35 of them to the British Museum. They are part of a 117-strong exhibition of his holdings entitled Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road. It will be the first time these prints have been seen in public; many are unique examples.

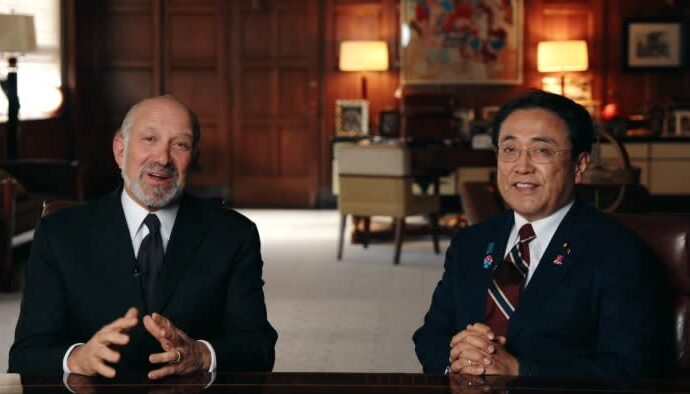

Medaugh was partly educated in Japan, and regularly returns to the country. Speaking from his New York, he is passionate about his subject, enthusiastically holding up illustrations of works for me to see. At one point, he tells me, works by Hiroshige were hard to come by, so he bought works by other artists. “Eventually, their prices went up relative to Hiroshige . . . So I sold them and bought more by Hiroshige!”

Having lived in Japan, and later having business ties with the Japanese financial community, I became interested in their art, and was quickly drawn to Hiroshige’s woodblocks — his scenes of mountains, rivers, birds and flowers have resonated around the world since the late 1800s. As time passed, I began to add birds and flowers (kacho ga) and fans (uchiwa) to my landscapes. In addition, there’s a social side to this: that of people who like objects. I find myself gravitating towards people who may not have Japanese prints, but may be interested in other things, be it Chinese porcelain or modern pictures. They are passionate about what they do; I like objects, and I like people who like objects.

I bought my first print in 1969 — it cost just $35! But it turned out to be by Hiroshige’s pupil, Hiroshige II. It was “Kiso Gorge in the Snow” from the series One Hundred Famous Places in the Provinces from the 1860s. Of course I initially thought it was a Hiroshige, but it was still a good one. It was not in great condition, but the colour was there.

As I started to go back more and more to Japan, I said to myself: I really do like these works, but most of the ones I see are awful. But then every once a while I would see a good one, and I would try to buy it. That is how my collection started. And I always keep things, so I still have that first print, even though I have obtained better versions since.

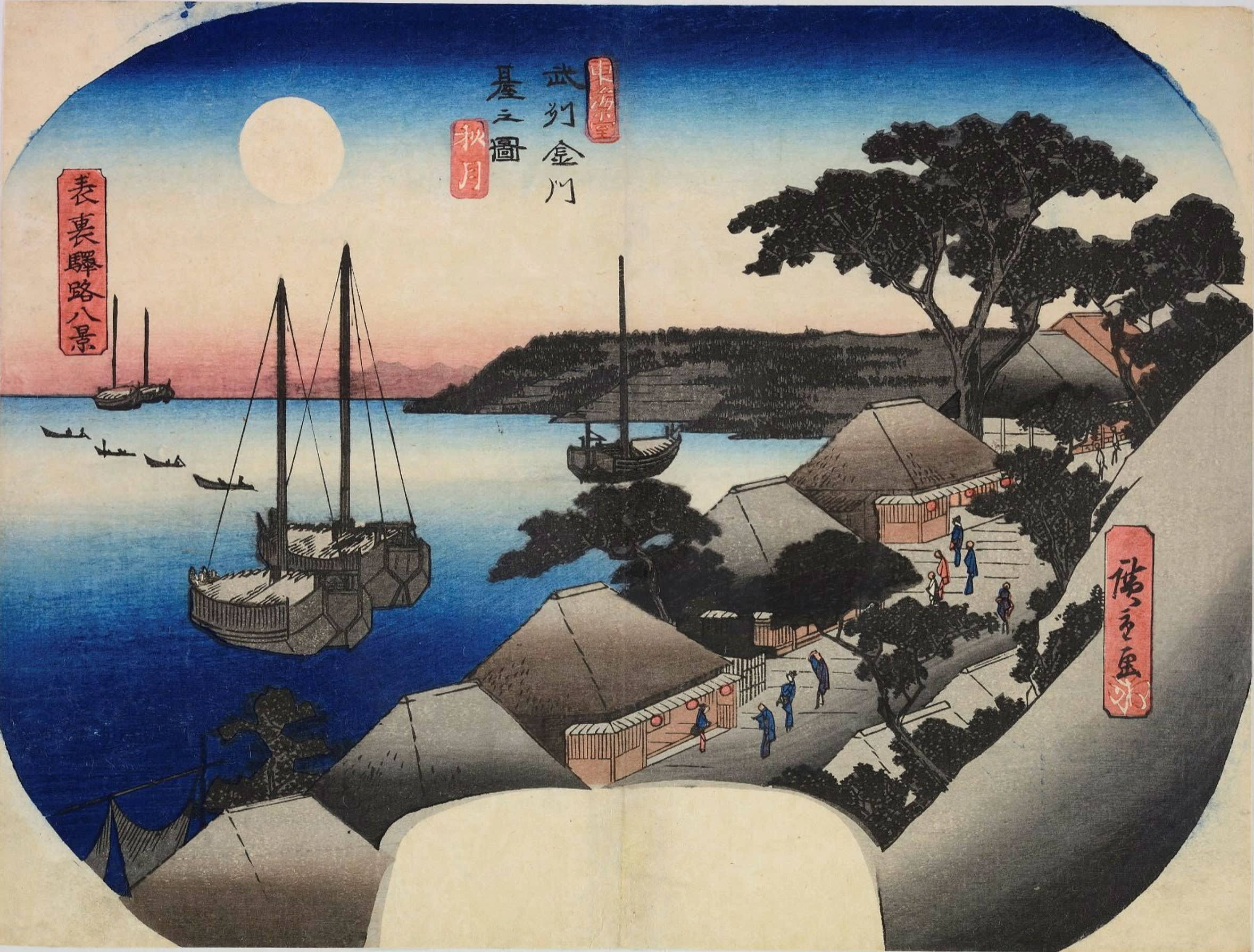

I have 800 favourites — but there are two works I am particularly attached to. Both are fans, and generally fans are extremely rare because they came from sample books the salesmen used. When the images became dirty, they would be ripped off and another one substituted. One is “Tokaido Autumn Moon; View from the Kanagawa Musashi Province”, which dates from the 1840s. It has such an atmosphere — the Moon is out and the Sun is just about to go down. I believe it is the only surviving example of this image.

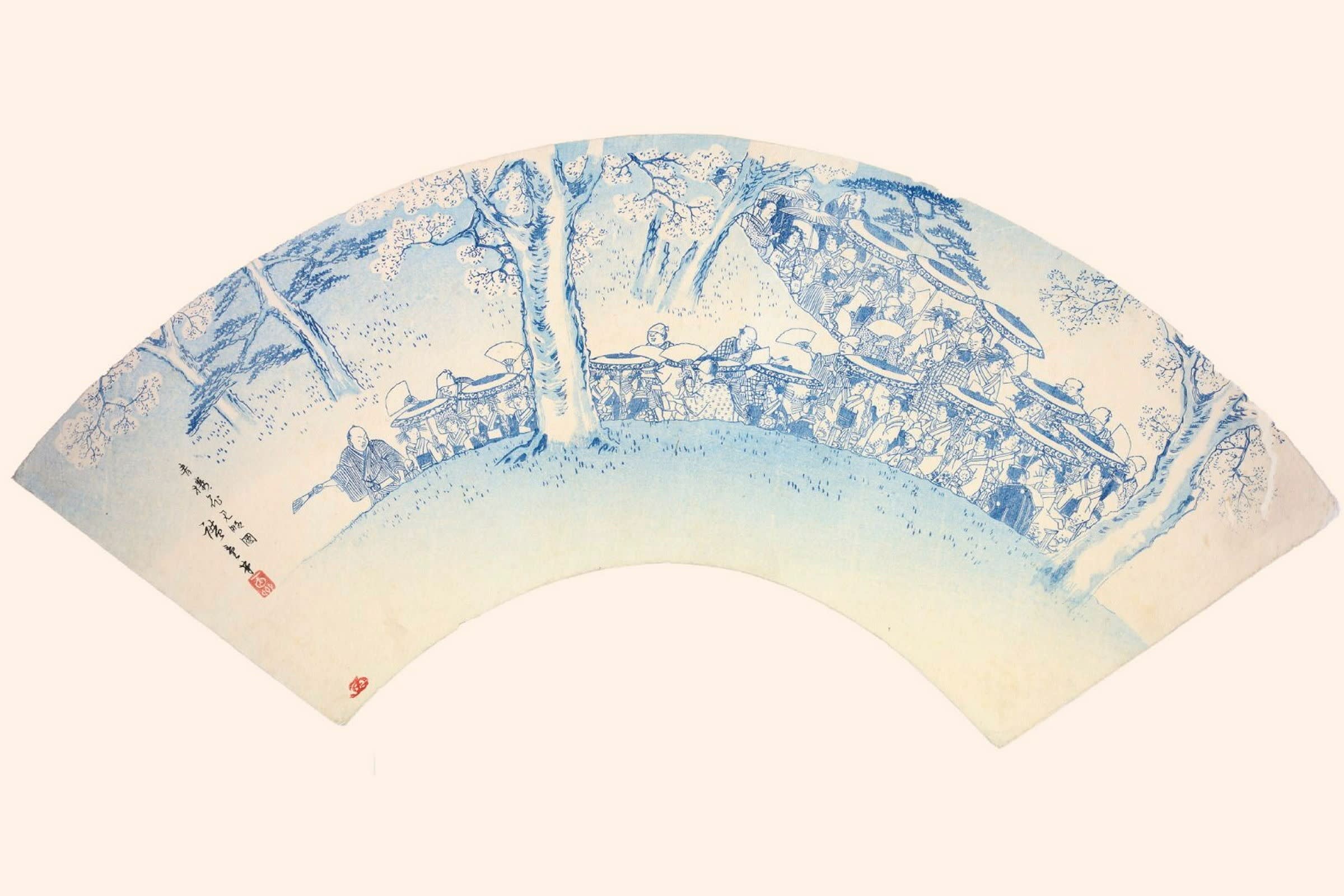

The other is a folding fan of a flower-viewing party, dating from the late 1840s or early 1850s. In it you see a procession from Yoshiwara winding its way through flowering cherry trees, and it shows the artist’s skill at drawing small figures, as well as his compositional ability. Because it is on thicker paper and so delicately coloured, it might have been a private commission.

I have a hanging scroll, a kakemono, from about 1840. It is immensely long, 7ft in all, although the painting itself is only about 4ft tall. The subject is “Bridge Enkyo of Kai Province in Moonlight”, also known as “The Monkey Bridge”. The painting is by Hiroshige, and there is also a print of that painting.

I started buying in the 1970s, when such prints were more accessible. Then, during Japan’s “bubble period” in the late 1980s, prices went crazy, so for a few years I decided to buy books, and I built up a library of about 300 or 400 books. I studied, I went to museums. But after 1990, prices started to go down a bit, so I was able to re-enter the market. Landscape scenes, especially the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, remain very sought-after. The main change has been the internet, which has broadened out the buyer base and increased competition. Now you get people from China and Russia, from Texas and Paris; so many more people are aware of Hiroshige prints today.

In 2005, Sotheby’s had an auction in London of the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, and one was of the O-Hashi bridge. It was the early part of the sale. I bid more than I should have, but someone else bid higher, setting a world auction record. I didn’t get it, although I did buy all the snow scenes later in that sale. But I never got that bridge scene . . .

My library includes a copy of the 1916 British Museum publication of its holdings of Japanese and Chinese prints, which identifies artists by signature and series of prints (such as Hiroshige’s 100 Famous Views of Edo). I believe the publication of this work was groundbreaking in the western world at the time. So the British Museum’s long-term record made donating prints to them very easy. It is gratifying to know that some of the prints I have spent 50 years collecting will be shared with the public for the future.

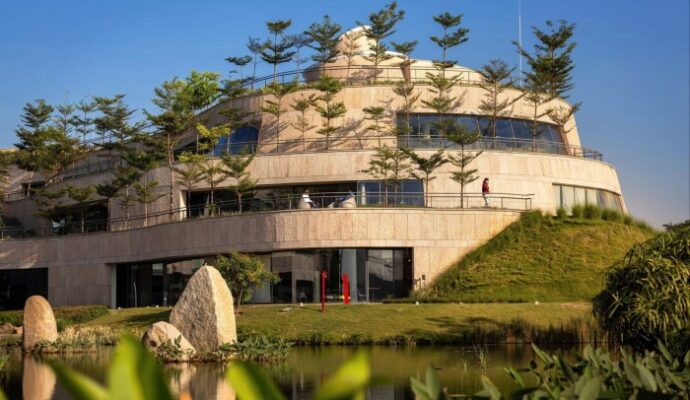

‘Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road’ is at the British Museum, May 1-September 7, britishmuseum.org

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning