Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In little over two weeks, India will commence what is billed as the largest exercise in electoral democracy in history. Close to 1bn people are expected to vote in its 44-day-long general election. Citing ancient traditions, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has repeatedly called India the “mother of democracy”. If so, an intensifying clampdown on opposition parties suggests this matriarch of representative government is in ill health, with worrying implications for the coming polls and what may follow.

A squeeze on free expression and opposition has been a feature of the rule of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party, especially since its second general election victory five years ago. Harassment, often by tax or legal authorities, has become common for government critics, be they independent media, academics, thank-tanks or civil society groups. The BJP’s muscular Hindu nationalism has eroded India’s tradition of secular democracy.

What is alarming now is a sharp step-up in state enforcement agencies apparently being used to stifle opposition parties and politicians as the election approaches. A stark example is the recent arrest of Arvind Kejriwal, chief minister of Delhi since 2015 and one of India’s most prominent opposition leaders. The leader of the Aam Aadmi party was detained after questioning by a body that polices economic crimes, over an alleged “scam” involving alcohol sales. Other senior officials of the AAP, which runs northern Punjab state as well as Delhi, have been held as part of the same probe.

Shortly before Kejriwal’s arrest the Indian National Congress, the biggest opposition party, claimed that its bank accounts had been frozen for weeks over a tax dispute. Rahul Gandhi, its most prominent figure, said the party had been unable pay for campaign workers, advertising and travel. Gandhi last year had a politically-tinged two-year jail sentence for defamation overturned by India’s highest court. Several senior members of other opposition parties have been arrested or harassed by law enforcement. The BJP says the arrests are not politically motivated but part of Modi’s efforts to root out corruption. Opposition parties counter that no senior BJP figure or Modi ally has been arrested.

At a rally in Delhi on Sunday, opposition parties united to demand Kejriwal’s release, and Gandhi accused Modi of “match-fixing” in the run-up to the election. The BJP denies the allegation that Modi and his party have used state agencies and authorities to stifle opponents or affect the election.

It is puzzling that the ruling party would even see a need to squeeze the opposition. Opinion polls suggest the BJP is cruising to a third five-year term. Its rivals have failed to present a compelling alternative, and the multi-party India National Developmental Inclusive Alliance, formed as a supposedly united opposition front, has been dogged by squabbles and defections to the BJP. Modi and his backers appear to have succumbed to a similar desire to achieve total political dominance as “strongmen” leaders elsewhere.

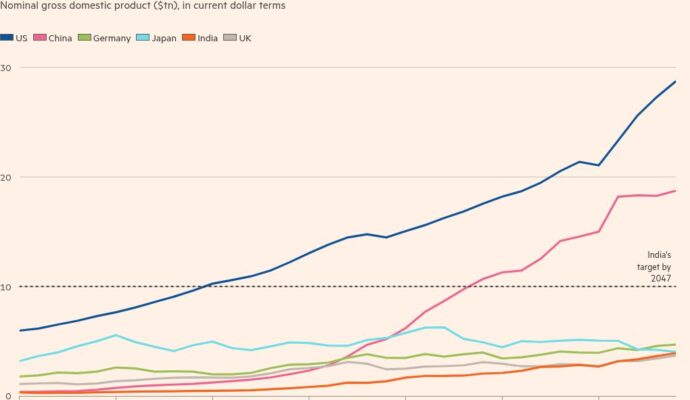

India is today one of the world’s largest and most vibrant economies. It has to manage its democracy according to its own culture and traditions. Some western democratic systems, in the US, the UK and elsewhere have been showing signs of strain. But there is an ever wider gap between Modi’s pro-democratic rhetoric and the reality. This matters not just for the rights and freedoms of its people. India’s attractiveness for investment, and as a geopolitical partner for countries wary of an increasingly authoritarian China, relies in large part on its image as a democratic, law-based state.

A desire to woo India has often led western democracies to hold their tongue over democratic backsliding. That shows signs of changing. After New Delhi summoned the top US diplomat to protest about criticism by Washington of Kejriwal’s arrest, the US repeated its concerns. Other democratic nations should be similarly robust. Preserving political freedoms is in the best interests of Indian growth and prosperity, and of the Modi government’s ambitions to enhance the country’s role as a leading member of the global community.