Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

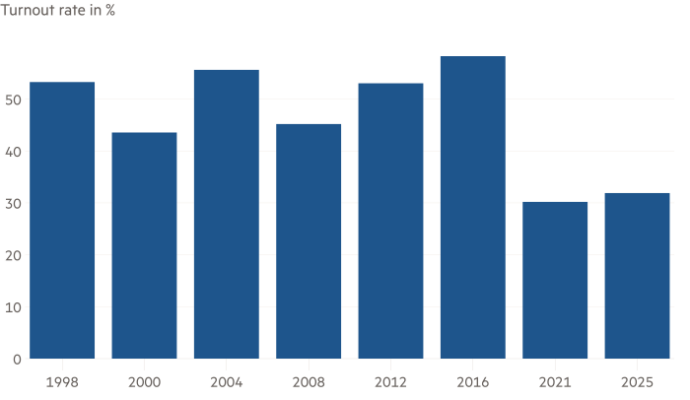

From sinister special forces soldier to cuddly dancing grandpa: Prabowo Subianto’s transformation is a testament to the malleability of public image. It helped him towards a decisive victory in Indonesia’s presidential election on Wednesday. With sample ballot results suggesting he has won an outright majority, Prabowo will avoid the need for a run-off in the summer, and the lengthy period of uncertainty that would have brought.

Prabowo is the clear choice of the Indonesian people and their choice deserves respect. Nevertheless, the former general will take office in the autumn with some doubts to assuage among foreign investors and the international community. Those include his commitment to human rights, following alleged involvement in abuses during Indonesia’s authoritarian past, a populist bent — in contrast to some orthodox economic policies that have served the country well — and the future role of his vice president-elect, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the son of current president Joko Widodo, widely known as Jokowi.

The historic allegations against Prabowo relate to the abduction and disappearance of activists during the transition to democracy in 1998. They are grave and cannot be conveniently ignored. Prabowo was dismissed from the military and banned from entering the US for two decades. The families of victims deserve truth and justice. Respecting Indonesia’s choice, however, means that these events must be considered in parallel with his presidency. Prabowo is now responsible for his country’s future, not just its past.

He revamped his image — busting out his dance moves at rallies and repackaging them on TikTok, in a slick social media campaign aimed at young supporters. But it was the presence of Jokowi’s son on the ticket, and the implicit endorsement of his popular father, that mostly explains why Prabowo ran away with the vote. Overall, the Jokowi years saw progress for Indonesia, investment in infrastructure, sound macroeconomic policies and reforms to improve the business environment.

Indonesians want this to continue. Prabowo should oblige. The country still has much work ahead to fulfil its immense economic potential. It needs to invest in its human capital if growth is to accelerate from 5 per cent a year to the 7 to 8 per cent achieved in the fastest growing economies. Easing regulation and reforming state-owned enterprises would help too.

Prabowo has made some populist spending pledges, such as spending 460tn rupiah ($29.4bn) to provide free meals and milk to schoolchildren. The problem would come if there is profligate spending. Indeed, Prabowo should not feel obliged to pursue the construction of Jokowi’s new capital city in the jungles of Kalimantan.

The presence of Jokowi’s son is both a blessing and a curse. It promises continuity and binds Prabowo somewhat to current policies. But it also raises the spectre of dynastic politics — not least because Prabowo is the scion of a prominent family himself — and the risk of tension between the two camps. Political dynasties are common in many democratic countries and need not be a disaster, but the danger comes if the interests of the dynasty start to outweigh the needs of the people.

For now, such fears are hypothetical. It is hard to predict how Prabowo will behave in office, but he comes to power at an auspicious time. There has been significant progress under Jokowi, the country’s minerals are in high demand for electric vehicle batteries and investors want alternatives to China. The ex-general must now show he really is a caring grandpa, live up to his predecessor’s economic legacy, build rather than limit his country’s young democracy — and take Indonesia forward.