In the late summer of 1936, the Van Der Wijck, a passenger ship steaming between two islands in the sprawling archipelago that made up the then Dutch East Indies, sank suddenly with great loss of life. The first mate had failed to close a porthole he had opened in harbour to alleviate the stench of rotting fruit; and in had poured the Java Sea.

The sorry tale has long been forgotten, not least given the catastrophe that engulfed the world just a few years later. But now it has been salvaged as the opening scene in, and central metaphor of, a long overdue and utterly compelling narrative history of the birth of Indonesia.

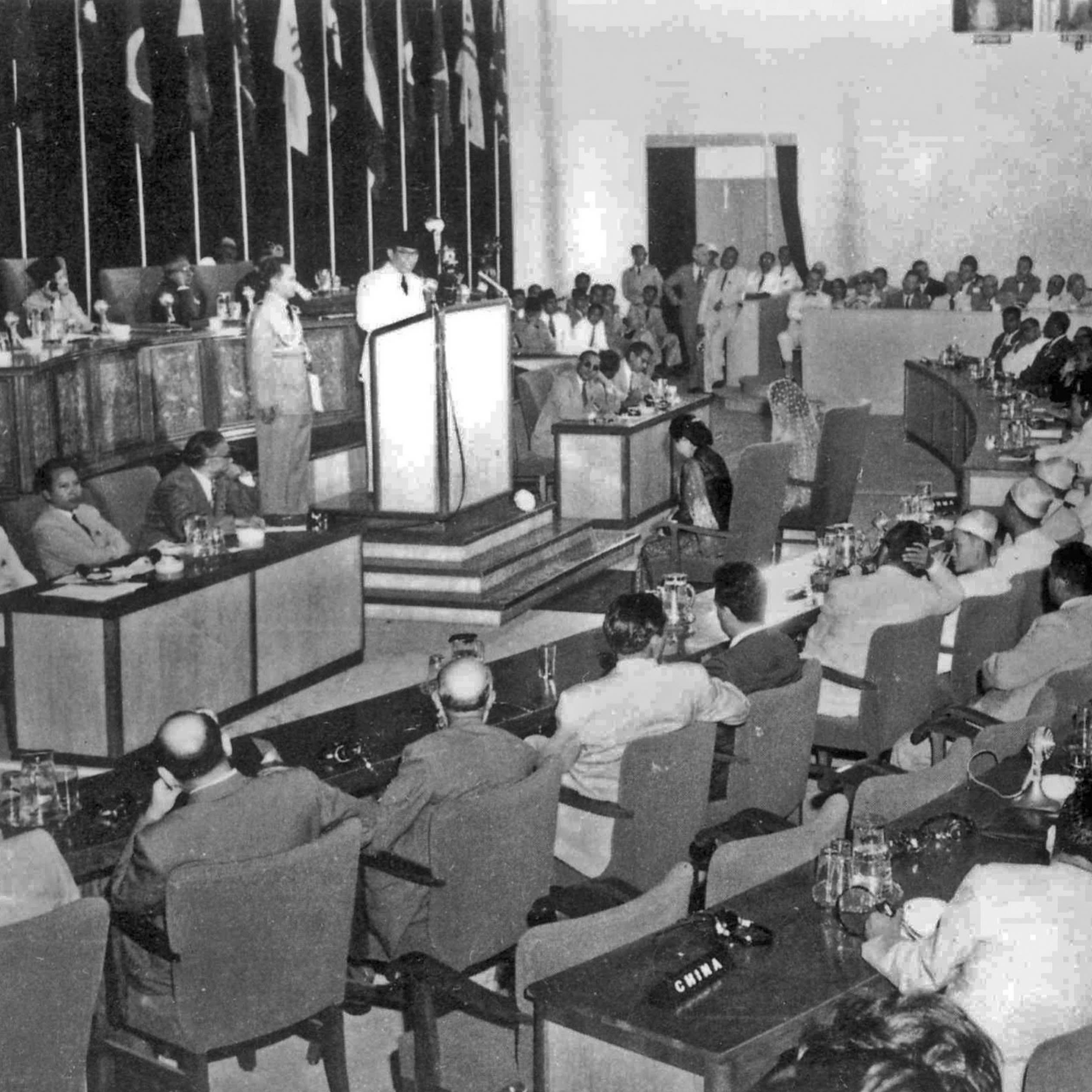

Revolusi by the Dutch-speaking Belgian historian David Van Reybrouck tells the epic story of Indonesia’s independence struggle, a four-year fight for freedom from 1945-49 that embroiled British, American and Dutch troops and cost 200,000 lives. The bravery and ultimate success of the freedom fighters — the first in a European colony to declare independence after the second world war — enthused anti-colonial movements around the globe in the ensuing four decades. In 1955, Sukarno, Indonesia’s first president, hosted in Bandung a summit of recently liberated nations that was the inspiration for the non-aligned movement. Its memory has been invoked in recent years as rising powers have sought to wrest from the west a greater role in the global economic and political architecture.

Yet this story has been overlooked in many histories of the postwar period and also of the end of the colonial era. As Van Reybrouck wryly observes, Indonesia — and its previous incarnation as the Dutch East Indies — is all too used to being out of the global spotlight. “It’s a very peculiar thing really,” he writes. “In population, it’s the world’s fourth-largest country after China, India and the United States, which are all in the news constantly. It has the largest Muslim community on earth . . . But the international community just doesn’t seem interested.”

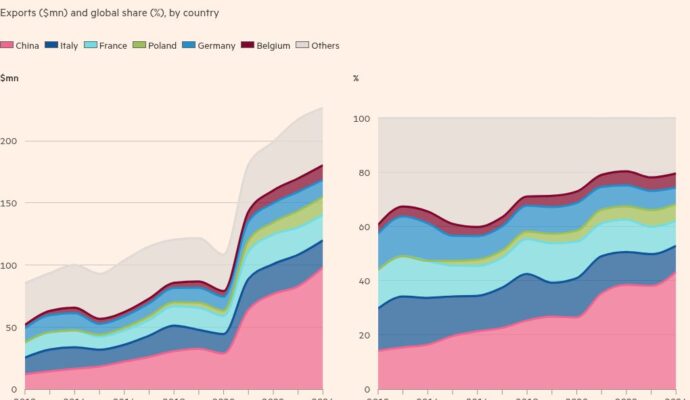

He is right that Indonesia attracts far less media attention than its size and influence merit, but investors are increasingly interested, in particular given that it is the world’s largest producer of nickel, the metal vital for electric vehicles and batteries. It’s just a decade since Indonesia was dubbed by a Morgan Stanley analyst as one of the “fragile five” emerging economies deemed particularly vulnerable to capital outflows. No longer.

Indonesia’s elections this month may not attract the headlines of other big polls this year, but they should. The outgoing president, Joko Widodo, has presided over a decade of steady growth and cannily steered a middle course between China and America. The question now is whether his likely successor, a former general with a slightly chequered record, will build on this and lead Indonesia further out of the global backwaters where it has broadly resided for so long.

Van Reybrouck wrote an acclaimed history, Congo (2014), of the centrepiece of his own country’s imperial shame. Now he directs his gaze on the record of the Dutch, the third-biggest European colonial power in the early 20th century after the British and the French, and it’s not a pretty picture that he paints.

For him the passengers on the Van Der Wijck — on different decks depending on their status — are a microcosm of the stifling stratification of race and class in the then colony. The Netherlands’ south-east Asian empire had been built up over 350 years. When the Van Der Wijck sank, the Dutch imagined they would be in charge of this archipelago of thousands of islands long into the future. And yet little more than a decade later they had to abandon their colony in humiliation.

Van Reybrouck sets the stage with a tart account of the Netherlands’ acquisition of its empire, driven primarily by the desire to corner the market of the fabled “Spice Islands”, in particular their cloves and nutmeg. He deftly captures the hypocrisy of the venture when assessing the directors of the 17th-century Dutch trading company that oversaw it in its early years. “The . . . seventeen pipe-puffing white-collared worthies who expressed themselves in baroque sentences, would have preferred the monopolies to be acquired with a little less bloodshed,” he writes, “but they continued to give Coen [one of the especially ruthless Dutch commanders] their full support because he was so good for the bottom line.”

In the following 300 years they took more and more from the local rulers, a history Van Reybrouck tells with piercing judgment, but his narrative really takes off in the 1930s with the Dutch suppression of the independence movement. By this time, its colony had become an even more treasured part of the Netherlands’ economy, not least given the discovery of rich deposits of oil — one of the primary goals for the Japanese when they invaded in 1942.

Remarkably, the author tracked down a number of surviving eyewitnesses from the 1930s and 1940s whose stories pepper his account. Interviewed in their nineties or even older, they offer a kaleidoscopic guide to the story that unfolds over a vast geopolitical canvas and yet never falters. They include Djajeng Pratomo, an economics student who was in the Netherlands when the Nazis invaded in 1940 and ended up in Dachau concentration camp before becoming an important figure in the independence struggle. Then there is Dick Buchel van Steenbergen, a Dutch soldier who was taken prisoner by the Japanese and was in Nagasaki on August 9 1945 when it was hit by the atomic bomb. He helped in the clear-up — and was interviewed by the author seven decades later at the age of 97.

For the colonised, the Japanese were initially a breath of fresh air; they expanded education and allowed expressions of nationalism denied under the Dutch. But they were brutal overlords, and as the war dragged on so conditions deteriorated. Four million civilians died during Japan’s four-year rule, mainly from starvation and disease, making Indonesia one of the worst affected countries in the whole war. “At first we were so good and then not any more,” Tomio Yoshida, a former Japanese soldier, tells the author from his hospital bed.

For the Indonesians, the defeat of the Japanese was merely the precursor to the main act in their fight for freedom. “Who would be the first to reach Deck 1 now that Japan had vacated it?”, asks the author, in one of many reprises of the colonial steamship metaphor.

The Dutch had no doubt they would be the ones back on Deck 1. It is remarkable to read how blasé they were about reclaiming their old turf. It is also shocking to read how savage they were in trying to cling on to it. Dutch soldiers committed appalling war crimes, repeatedly massacring civilians. As the Netherlands finally admitted defeat, a Dutch observer says: “What is left to us is shame at all our narrow-mindedness, incompetence and conceit.”

The British too do not emerge nobly from scrutiny of the year when they were caretaker rulers overseeing the departure of the Japanese. And then there is the cynical toing and froing of America as it treats Indonesia as a pawn on its anti-communist chessboard in the early years of the cold war with the Soviet Union.

When Revolusi was published in the Netherlands four years ago it was a bestseller. Now a fine translation by David Colmer and David McKay deservedly brings this story of the triumph of the human spirit over the avarice of a colonial power to a wider audience. It is as intricate as the waterways of the archipelago and yet it hums along, like a steamer on the Java Sea, propelled by the stories of its astonishing cast.

Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World by David Van Reybrouck, translated by David Colmer and David McKay, Bodley Head, £30, 656 pages

Alec Russell is the FT’s foreign editor

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen