But they have warned more improvements are needed, as constitutional limitations like no foreign judges, an overall lack of expertise in foreign-related law and the potential interference of the ruling Communist Party cast doubts on the courts’ impartiality and independence.

China’s Supreme People’s Court first set up two national-level international commercial courts in 2018 to handle belt and road-related disputes – one in the southern city of Shenzhen, Guangdong province, to solve maritime-based cases and the other in the western city of Xian, Shaanxi province, to process land-based cases.

At the belt and road judicial cooperation forum in October, the top court’s vice-president, Tao Kaiyuan, said “providing both domestic and foreign parties with more equitable, efficient, convenient and cost-effective dispute resolution services” had become a shared goal for countries taking part in the initiative.

Following the top court, the first municipal-level international commercial courts were formed – one in 2020 in Suzhou, a manufacturing hub in the eastern province of Jiangsu, then one in Beijing in 2021.

Five more cities followed in 2022, with courts set up in Chongqing and Chengdu in the southwest as well as Quanzhou and Xiamen on the east coast and Nanning in the south. This year, four more cities in wealthy eastern provinces have also created the courts – Hangzhou, Ningbo, Wuxi and Nanjing. Changchun in northeast China, near the Russian border, also joined this year.

“There is a strong signalling dimension to the new courts, the message being, ‘We’re open for business’,” he said.

Hong Kong lauded for its potential to boost legal sector ties with Asia, Africa

Hong Kong lauded for its potential to boost legal sector ties with Asia, Africa

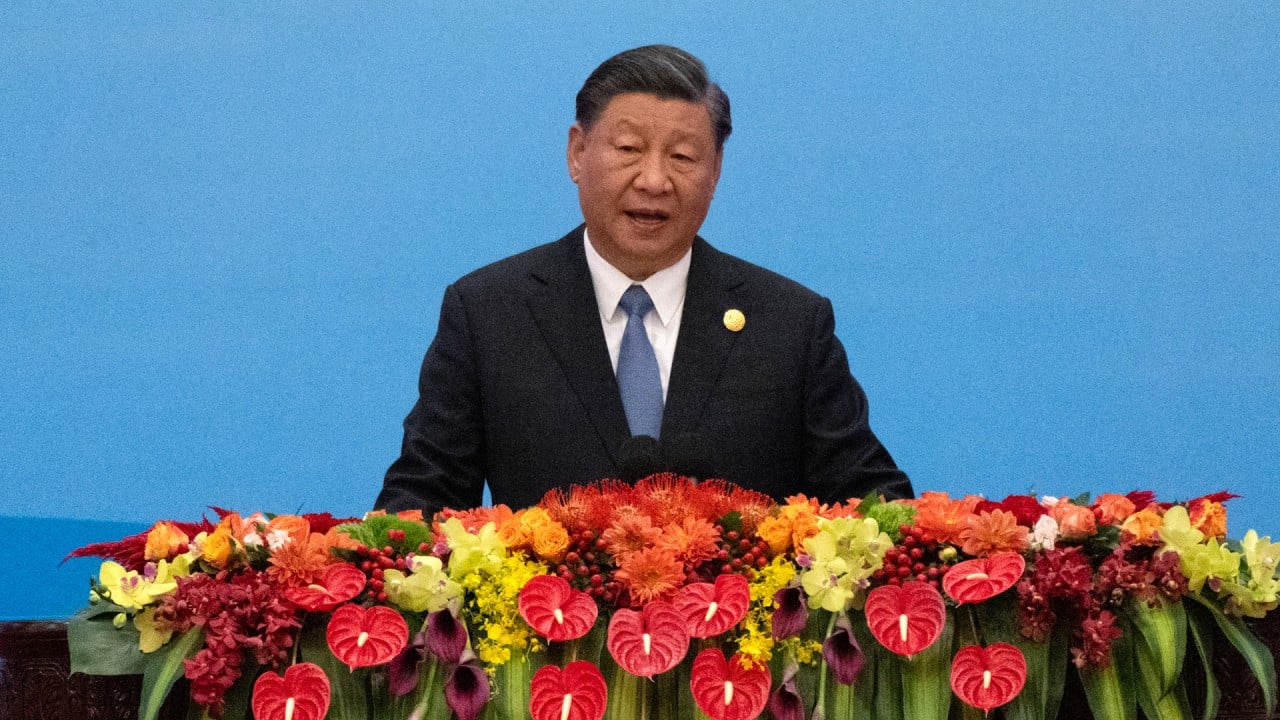

Beijing declared it would build a “top-tier preferred destination” for resolving international commercial disputes in a plan packed with more “opening up” measures endorsed by the State Council in late November.

But despite the Chinese leadership continually vowing to stay committed to opening up, foreign investors have not been convinced due to its overarching priority in national security.

Erie said the courts may have been more “performative than substantive” as they derived from the choice of the country’s ruling Communist Party and constitutional limitation.

“Ultimately, the use of courts derives from party choice. Litigants need to feel that the courts are impartial and independent forums. Until then, such initiatives will remain more performative than substantive,” he said.

A way around this, Erie said, would be for the courts to serve as legal “carve-outs” which would function differently to the broader Chinese legal environment.

He added that some of the initiatives had been labelled as part of the “foreign-related rule of law”, which is partly a response to the US extraterritoriality.

Similarly, James Zimmerman, a partner at the Beijing office of US law firm Perkins Coie LLP, said the new courts did not provide an “attractive dispute resolution forum” for foreign business, with doubts cast over the courts’ lack of practical international experience as well as their ability to remain impartial.

“Most foreign lawyers would likely steer their clients away from litigation in any court in mainland China, except in situations where they are required to, or have no other alternatives,” said Zimmerman, who has practised law in China for over two decades.

However, Gu Weixia, an associate law professor at Hong Kong University, said that assuming having Chinese judges would lead to partiality in ruling decisions was a “perception” only. She said other countries with similar civil law systems, such as Germany, also only used judges of their own nationalities.

She said there was no concrete evidence to support such a “perception” based on her observation of the court in Suzhou, which has operated the longest compared to other city-level courts.

“We cannot see that any rulings have been unjustly influenced by Chinese judges,” Gu said.

The Suzhou court hailed its first case of enforcing a ruling made by the foreign arbitration institution of Ukraine as a typical example showing Chinese courts protecting the equal legal interests of both Chinese and foreign parties, according to state-run Legal Daily.

In the case, a Ukraine company paid US$80,000 to a Suzhou material supplier but never received the goods, and the Suzhou business did not return the prepayment even after a Ukraine arbitration institution ordered it to do so, it said.

The Ukraine company applied to the Suzhou International Commercial Court in 2021 to enforce the ruling made by a Ukraine arbitration institution, and the Suzhou court decided to recognise and enforce it after “carefully examining if this follows the New York convention” – an arbitration code China signed up to in the 1980s, it said.

Xi calls legal backing on foreign affairs an ‘urgent task’ for China

Xi calls legal backing on foreign affairs an ‘urgent task’ for China

The default proceeding law in China’s international commercial courts is Chinese law, but parties could also choose a foreign law as their governing law by agreement.

Suzhou has accepted more than 3,000 cases involving around 53 countries and regions, including the United States and Japan, and disputes covering areas in trade, finance and cross-border investment, according to a Legal Daily report in late November.

Gu said the courts, as part of the national judicial infrastructure, reflected the country’s geopolitical and geoeconomic ambitions. They are created out of need, as China expands its global presence, with more Chinese companies going abroad and foreign investment increasing due to the massive Belt and Road Initiative.

She also sees a demand for city-level courts to process the large number of small and medium-sized foreign commercial disputes.

Gu said China’s creation of international commercial courts aligned with the global trend. Similar courts have emerged in post-Brexit Europe, Kazakhstan and the United Arab Emirates in the past decade, and they have been a “game-changer” in the international dispute resolution market, offering more flexibility to avoid local national courts and legal systems.

But she also agreed there was “certainly room for improvement” in terms of making the judicial system more “international” as not all judges have proficient legal English. According to Gu, China could also take lessons from Germany and use non-legal professionals, like businesspeople, as jurors in the future.