Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is senior economist at Nomura Securities

Efforts have been under way in Japan in recent years to switch the approach to river water control to tackle the growing risk of floods as climate change intensifies. The shift offers a neat parallel to what the Bank of Japan is trying to do to adjust its bold experiment in monetary policy.

The shift in water control has been away from a reliance on fixed infrastructure such as dams and embankments under a river management authority. These have sometimes proven unable to cope with unexpected increases in rainfall and river flows. Instead, the newer approach seeks to minimise damage by allowing a limited and intentional flow of water outside embankments while using wide-ranging facilities such as fields and infrastructure in river basins as a buffer.

We think the BoJ’s recent moves at its October 30-31 monetary policy meeting to increase flexibility of its bond-buying programme to contain yields are based on the same concept.

In July, the BoJ had made changes to the programme, known as yield curve control. This was initially launched in 2016 by former BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda as an attempt to stimulate the economy. If Japanese government bonds yields rose above 0 per cent, it would buy more JGBs. And it bought a lot of them — it now owns more than 50 per cent of JGBs, up from less than 10 per cent in 2010. It later increased the target ceiling to 0.5 per cent and in July it was further raised to 1 per cent.

This was to ensure the “embankment” of yield control did not collapse or was overrun. However, yields rose faster than expected, pushed by strong upward pressure from higher US long-term interest rates.

The October measures can be described as allowing the embankment to be breached to a degree but in a limited way — broadly equivalent to withdrawing the policy of bond purchase operations on each trading day at the 1.0 per cent level.

This does indeed mean it is possible that depending on the conditions, the river water could flow over the embankment to the outside. However, we think two misunderstandings on this must be avoided.

First, a decision has not been made to do away with river water control or a judgment made that it is no longer necessary. In other words, although the BoJ is clearly taking a more flexible approach than before, it has not changed its stance of aiming to control long-term interest rates to achieve its price stability target and for that to be accompanied by wage growth. Some market participants have assumed the BoJ has de facto scrapped YCC. We believe it is not yet in the case.

Second, and a more important question, is that if the “river water controls” were done away with, would that mean that the position of underlying interest rates has changed?

It could be that the current “surging river” in Japanese long-term interest rates is only the result of “climate change” — in other words completely the result of the strength of upward pressure from US long-term interest rates. Then a major change in interest rates is unlikely once these external factors came to an end.

A fundamental change in the position of the river flow would only be possible if the growth potential of the Japanese economy improved and the underlying inflation rate increased along with that.

That might be one reason the BoJ did not clearly say that it had taken measures equivalent to river basin water control at its October 30-31 meeting.

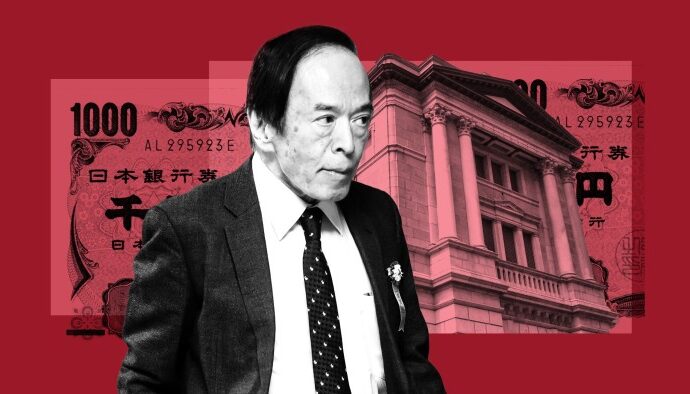

There are increasingly signs of what BoJ officials, including governor Kazuo Ueda, call a virtuous cycle of wage and inflation. We expect a slightly higher wage hike in next year’s Shunto (a collective wage negotiation in spring) than happened in this year’s. We forecast pay increases of 3.9 per cent apiece in the fiscal year to March 2024 and 2025, ahead of the 3.6 per cent recorded in 2023. Several major enterprises already announced even higher wage rises for their employees. This should further boost consumer spending, along with the Kishida administration’s $113bn stimulus programme of cash handouts and tax cuts.

With the economy remaining on modest recovery track, we forecast real GDP growth of 1.4 per cent for this fiscal year, 0.5 per cent for 2023-24 and 1.0 per cent for 2024-25.

The longer-term growth potential of the economy, which is another important factor for gauging the axis of river flow, has not yet shifted upward significantly. But we think the BoJ might have had an eye on the possibility that the flow of the river has fundamentally changed. We think there is 60 per cent probability of the scrapping of YCC in the second quarter of 2023-24 (potentially in April).