“If they really were worried about crisis management, they wouldn’t be doing the dangerous air intercepts they’ve been doing, they wouldn’t be doing the dangerous maritime intercepts they’ve been doing.

“I don’t believe that they think crisis management is something that is in Beijing’s interest right now.”

Initially, US analysts said, they believed the close-in manoeuvres involving Chinese fighter jets and naval vessels making rash moves at high speed in and around the South China Sea were driven by reckless “hotdog” operators.

Over 180 ‘coercive and risky’ PLA incidents against US since 2021: Pentagon

Over 180 ‘coercive and risky’ PLA incidents against US since 2021: Pentagon

But as the number and regularity of incidents increased, many said they concluded this was something close to an official policy.

But analysts also point out how it would look if the roles were switched.

“Detente goes only so far,” said Dominic Chiu, a senior analyst with Eurasia Group. “If the situation were reversed, it is hard to imagine the US would be inert if China’s military operated 13 nautical miles off the coast of Los Angeles on a daily basis.”

The US has been pushing hard for some sort of guard-rail agreement but it should be realistic. “Don’t expect Xi to restore the US-China military hotline this week,” said a report by the Brookings Institution released Monday.

“It is fine for Biden to make the request. But he should expect ‘no’ to be the answer – and avoid conveying too much US anxiety over the two nations’ military tensions in the Western Pacific.”

Analysts said that from China’s perspective, offering guard rails to the Americans was akin to a car insurance policy that made a driver more reckless knowing they were covered.

“The Chinese hate the idea of guard rails or efforts to manage crises because they think such things simply create a floor under US provocations, allowing the US to push even further without creating a conflict,” said Michael Swaine, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

US reconnaissance plane passes through Taiwan Strait, closely watched by Chinese jets

US reconnaissance plane passes through Taiwan Strait, closely watched by Chinese jets

It wasn’t always this way. In 1998, the US and China launched the Defence Policy Coordination Talks and signed the Maritime Military Consultative Agreement to enable ship and aircraft operators from both sides to communicate regularly. This was followed in 2014 by the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea.

But these have atrophied as China’s military ambitions and capability have expanded, Beijing has adopted more muscular foreign policies and tensions have increased.

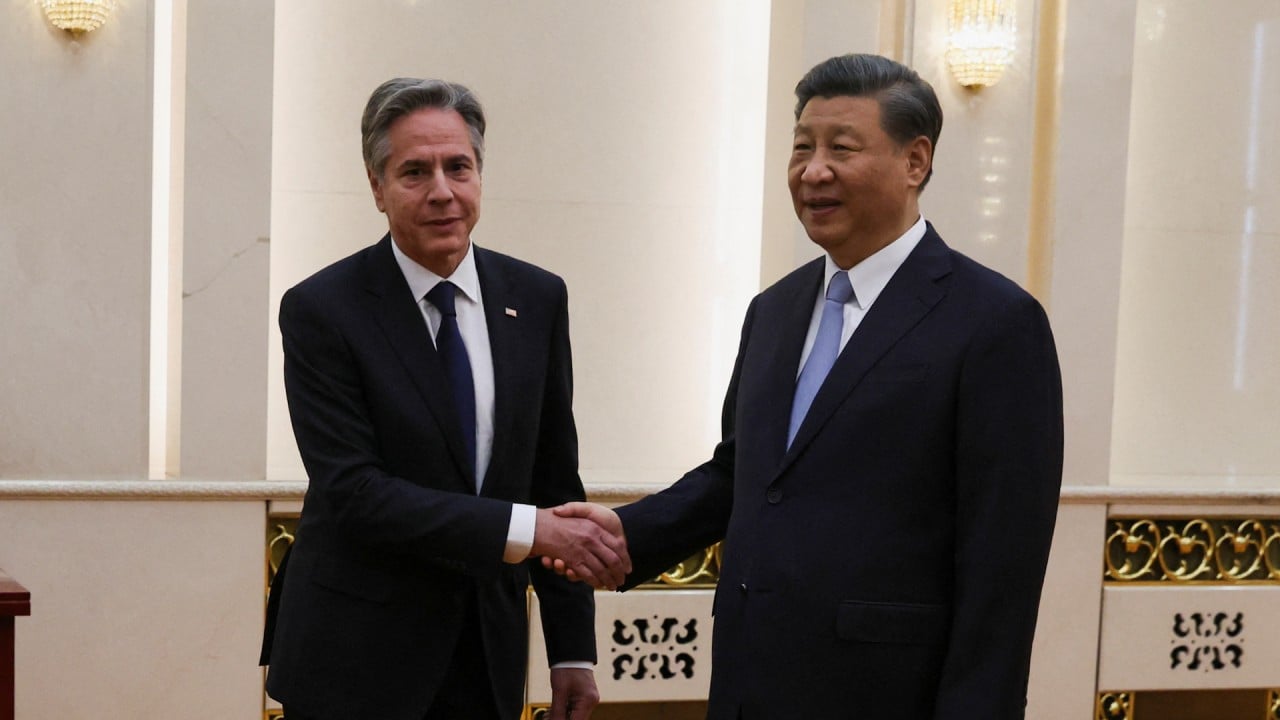

In advance of the Xi-Biden meetings, there has been a modest warning.

While the odds of unintended conflict remain small, the risk is growing as communication and crisis management falter, trust craters, more ships and planes inhabit a smaller area and the ability to quietly manage it becomes politically difficult.

The two nations now face the greatest risk of misinterpretation or an accidental air or sea collision spiralling out of control since 2001, when Chinese pilot Wang Wei was killed and a US EP-3 spy plane forced down over Hainan Island.

There have been some signs of easing, although these may be largely tactical as China grapples with mounting domestic problems. Austin was invited to China’s annual Xiangshan security forum – he opted not to go given that Beijing is currently without a defence minister – and rare if inconclusive talks were held last week on nuclear arms control.

Former officials who have been involved in negotiations over guard rails say Beijing insists that any such talks include a discussion of the policies that create the potential for such a crisis.

‘Malicious, provocative’: China slams Canada over South China Sea mid-air encounter

‘Malicious, provocative’: China slams Canada over South China Sea mid-air encounter

“For them, this consists solely of US policies,” Swaine said. “And for that reason, the US largely rejects such ‘crisis prevention’ discussions.”

Even so, analysts say, you have to start somewhere.

It remains to be seen whether any potential agreement for better military communications will result in fewer near-miss incidents, according to David Finkelstein, vice-president with the Centre for Naval Analyses.

“That said, without moving forward to re-establish dialogue on both strategic and operational level issues, no progress on that front will be possible,” Finkelstein, a former adviser to the US defence secretary, added.

“There cannot be a stabilisation of the overall bilateral relationship without a military component.”