Earlier this year, Mahendra Patra took out a Rs1.8mn ($21,600) bank loan to install rows of rooftop solar panels on his three-storey factory on the outskirts of Bhubaneswar, a city in India’s eastern state of Odisha.

Inside the factory, some 30 employees run looms churning out sturdy blue nets for the coastal fishing industry. Since the installation, operations have begun running on solar energy during the day, lowering Patra’s power bills. Sometimes the plant feeds surplus electricity back into the grid.

Patra is something of an outlier in Odisha. The state of 40mn people holds the largest coal reserves in India and the local economy relies on the fossil fuel. Odisha is also geographically unsuitable for solar farms due to its stormy weather, erratic sunlight and dense forests.

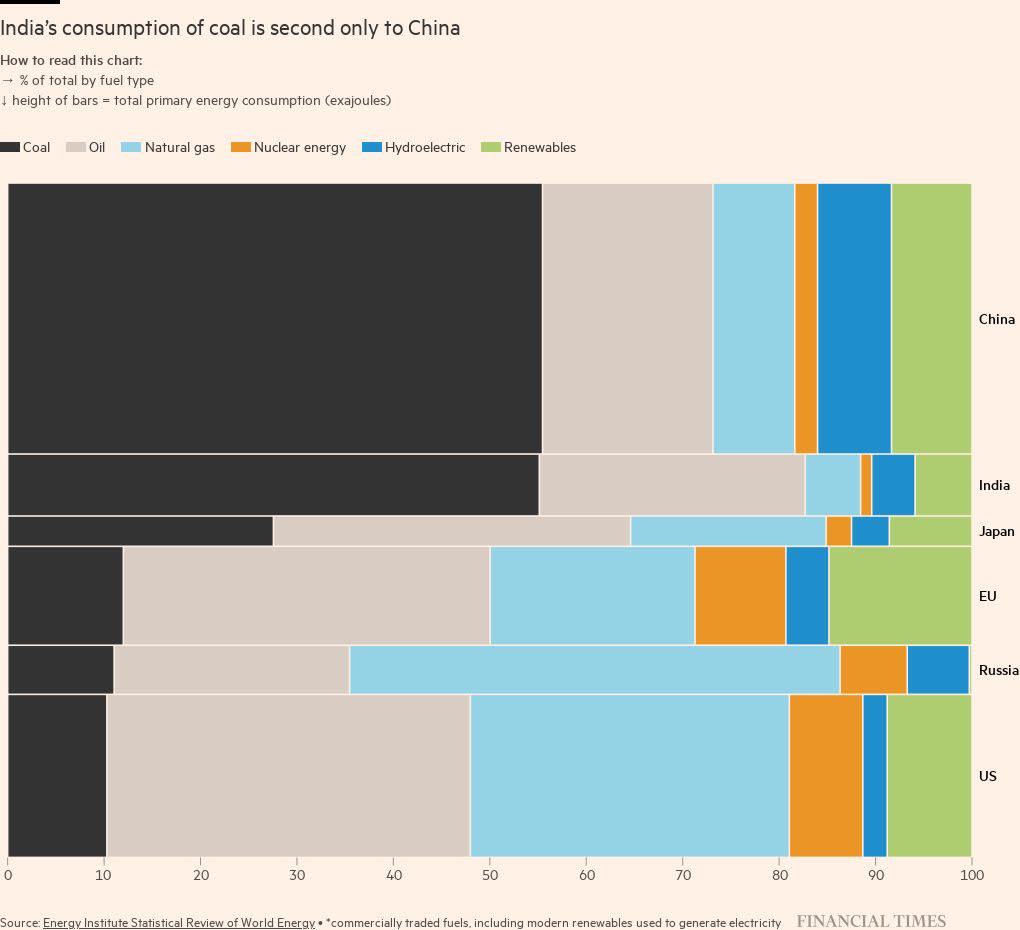

But efforts within the state — such as Patra’s panels — encapsulate India’s uphill struggle to wean its fast-growing economy off fossil fuels. Coal currently accounts for around three-quarters of the nation’s power generation. While per capita energy consumption in the country, the world’s largest by population, is well below the global average, demand is expected to grow more over the coming decade than anywhere else.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has laid out an ambitious target to build 500 gigawatts of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030. India has also announced billions in subsidies to manufacture clean-energy technology and wants to become a leading green hydrogen exporter.

Demand for renewables is growing and, in Odisha, the state has launched a series of initiatives designed to capture a sliver of the investment pouring in to the energy transition.

“This is something that is not an option: we have to go for green energy,” says Nikunja Dhal, Odisha’s energy secretary. “Odisha, because of the higher carbon intensity of its economy, needs to be more aggressive . . . We understand that.”

Yet India’s energy transition is complicated by intractable problems, from the difficulty of acquiring land for solar and wind farms to deep financial distress in its power system, which slows new investment. While demand is surging, millions still lack access to reliable electricity. Authorities see the expansion of polluting industries like steel and cement as essential to creating jobs and economic growth.

This means that, even as they invest in renewables, coal-belt states such as Odisha are opening more mines and power stations that will leave India dependent on coal for decades to come.

India’s plans are in focus ahead of the COP28 summit in the UAE in November. India was among multiple countries including China that successfully resisted a plan at the COP summit in 2021 to phase out coal completely, arguing this would jeopardise its energy security. Modi’s government says that it is the responsibility of rich countries who caused the bulk of historic emissions to stop polluting.

Research group Climate Action Tracker says that while India is “a world leader in new renewable energy”, its targets are not consistent with the sorts of policies needed to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

For Indian industry, speeding up the growth of renewables is vital to attracting the vast sums of money starting to flow into green projects around the world.

India “needs to decarbonise to be competitive”, says Jayant Sinha, a member of parliament with the ruling Bharatiya Janata party who represents a coal-producing constituency in Jharkhand. “The whole net zero story hinges on renewables coming up fast enough . . . The issues are well understood, but finding a pathway is very tricky.”

Green gamble

The prospect of India becoming a major green energy producer has prompted a scramble among international investors eager to buy in. Foreign direct investment into non-fossil fuel energy last year rose 40 per cent to $2bn from a year earlier, according to government data.

Sovereign wealth funds and pension funds have poured billions of dollars into green energy projects, split among both traditional coal power producers such as Tata Power and new generation renewable groups like ReNew and Avaada.

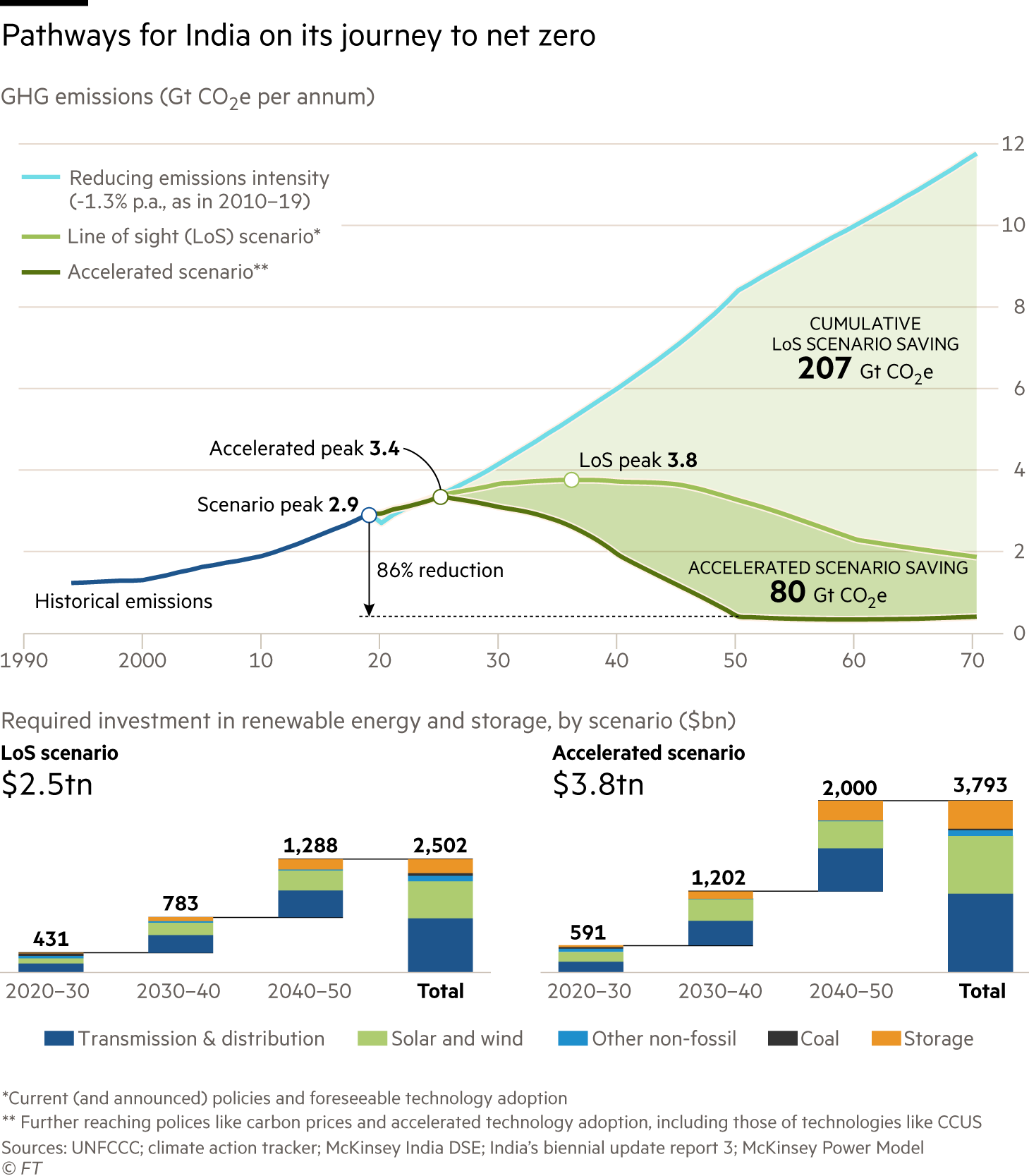

The sums required to convert India’s economy are vast. McKinsey estimates India requires a minimum of $2.5tn in renewable investments to have a hope of achieving its pledge to become a net zero carbon emitter by 2070.

The sheer expense means India risks falling behind its renewable pledges. Authorities earlier this year announced that they planned to more than double the pace of capacity construction to around 50GW a year. The jump is “very, very ambitious”, says Praveer Sinha, managing director of Tata Power. “It’s going to take time.”

Accelerating the transition up will require solving problems that have stumped Indian policymakers for decades.

High among them are electoral promises to provide cheap electricity, which have left the largely state-owned power utilities drastically unprofitable. This has led to chronic under-investment in the grid, widespread loss of electricity and frequent blackouts. Utilities are often unable to pay their power suppliers, including renewable companies. As of June last year, there was a Rs1.4tn ($16.8bn) backlog of delayed payments, according to CreditSights, a Fitch-owned credit research company.

A scheme introduced last year, to force utilities to pay up by imposing additional fines on delayed payments, has shown promise, helping to more than halve outstanding dues.

But one of Modi’s biggest bets, that India can develop a green manufacturing base, is yet to pay off. Under its production-linked incentive subsidy scheme, first introduced in 2020 to spur the manufacturing of products such as electronics or pharmaceuticals, India has begun committing billions of dollars to build solar modules and electric-vehicle batteries.

Vineet Mittal, the chair of green energy group Avaada, which is building a solar panel plant under the programme, says that it could be a “game changer for Indian industry”.

Yet whether it can keep pace with countries such as the US and China is less certain. Production of parts under the scheme has mostly not started yet, and India’s subsidies are dwarfed by those elsewhere. The US, for example, is extending subsidies of around $3 for every kilogramme of green hydrogen that will be produced, according to estimates, compared with less than $1 in India.

Equity investors betting on India’s renewable companies have also had to deal with unwelcome surprises. Adani Green Energy’s share price has dropped 46 per cent this year, following short seller allegations of fraud that the company denies. In a separate incident, shares in another prominent group, Azure Power, are down 79 per cent this year after the company said it found evidence of data “manipulation” and other wrongdoing.

Tata’s Sinha acknowledges that incidents like these have created “challenges” for investors. “There is a concern, and rightly so also, that there are not very many groups or very many companies who will have the type of core competence or the DNA to do such large projects and give returns on a consistent basis,” he says.

Dream of diversification

The building of renewable infrastructure has so far been concentrated overwhelmingly in India’s southern and western states such as Gujarat, a desert region that benefits from both higher solar radiation and ample barren land.

For coal-producing states like Odisha, which are already among the country’s least developed, the prospect of declining fossil fuel use poses an existential threat. Across the mineral belt, coal royalties account for as much as 12 per cent of state revenues and some 25mn livelihoods depend on the industry, according to Rohit Chandra, an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi who specialises in energy.

“Economic diversification is top of [coal-belt state leaders’] minds,” Chandra says. “To what extent any of this is anchored in anything technologically or economically realistic is another question altogether.”

Preparing revenue-generating alternatives to coal for states such as Odisha is at the heart of calls to enlist multilateral development institutions and investors for a “just” transition that protects vulnerable economies and jobs. “It is important that our brothers and sisters of the global south are not left behind,” Modi said at a G20 event in July.

“As coal production goes down, the renewable [sector] has to go up and we have to rebuild the whole of the power sector — building new power plants, windmills, solar, pump storage,” said Sajjan Jindal, the chair of industrial group JSW.

To help attract investment, Odisha in 2021 sold its lossmaking electricity utility to Tata Power, which committed to invest Rs50bn into transforming the electricity distribution infrastructure, from upgrading the thousands of faulty meters across the state to repairing power lines.

The contentious privatisation, which was criticised by local opposition parties as a selling out of key public goods, has shown some early results. After an unpopular early price increase, the company says that the amount of electricity lost to technical problems or illicit connections has fallen from 28 per cent to 18 per cent, while the frequency of blackouts has reduced.

Sanjay Banga, the head of Tata Power’s distribution business, says that a healthy utility will be the foundation of the state’s energy transition. “If the [utility companies] are not financially sound then the entire [renewable and thermal energy] generation plan is anyway going to be hampered because no one is going to set up a generation plant,” he says.

The share of renewables in the state’s energy mix has slowly been growing. Last year, Odisha signed a power purchase agreement for around 1,000MW of wind power capacity, and non-fossil fuel sources, including pre-existing hydropower projects, now account for around a third of its electricity in its grid. State authorities say they plan to build 10GW of renewable power capacity by 2030. Tata Steel and Avaada also this month announced plans to build a green ammonia plant in the state.

Coal pipeline rumbles on

A few hours’ drive from Odisha’s state capital Bhubaneswar, a drastically different picture of India’s energy ambitions emerges.

In Angul, the state’s mining hub, opencast mines excavate vast quantities of coal every year. Coal dust covers nearby greenery and the roads are frequently clogged by trucks transporting the fuel.

This activity shows no signs of slowing down. iForest, a think-tank which last year proposed an energy transition plan for Angul, estimates that coal production may triple before production peaks in 2033, with several new mines set to open.

India as a whole also has approximately 65GW worth of new coal power plants under construction or being planned, according to non-profit Global Energy Monitor, with three projects approved only this year. This gives India the second-largest new coal pipeline in the world after China and ahead of countries such as Turkey and Indonesia. Companies including Adani Group continue to aggressively invest into the country’s coal sector.

“Right now there’s no other option,” says Prakash Ravidas, a mine supervisor working in a local mine. “We don’t see what the alternative could be . . . Without coal, nothing will work.”

The reality is that even if India meets Modi’s 500GW non-fossil fuel capacity target, renewables are only expected to account for around half of power generation in 2030. With India’s energy demand growing as much as 6 per cent a year, this means India will probably need to consume more coal than it currently does by the end of the decade.

“Will we still be dependent on coal? Yes, we will be,” says Sumant Sinha, the chair of ReNew. “India’s a massive country and growing rapidly . . . [The government] can’t afford to have growth getting stymied on account of lack of power. That’s what they’re struggling with.”

Critics argue that the dramatic fall in the price of renewable energy over the past decade, which can now be cheaper than coal-derived power, should push authorities to be more aggressive in phasing out the fossil fuel.

The biggest obstacle, however, is the lack of power storage. While coal plants can run 24 hours a day, the intermittent supply of solar and wind means it must be stored in batteries in order to provide continuous power.

While India’s National Electricity Plan expects the country will build enough storage by 2027 to avoid adding yet more coal plants to its pipeline, battery technology is prohibitively expensive and authorities are considering new subsidy schemes to bring down prices.

“[For] as long as we don’t have low-cost storage available, we need to have base power, and base power has to come from coal,” says Dhal, Odisha’s energy secretary.

States such as Odisha face more immediate pressures simply keeping the lights on. Ranjita Naik, who lives in a small village in central Odisha, only started getting electricity around a decade ago. The precarious supply, which in the past would cut out for a day or more at a time, is now regular enough for her family to power a TV, fan and a single lightbulb in their brick and thatched-roof house.

The growth in basic amenities like these contributed to the 17 per cent growth in Odisha’s grid power demand in the past year. Managing this demand is becoming harder as the state is buffeted by increasingly violent, cyclonic storms and heatwaves linked to climate change.

It is hard economic realities like these that will ultimately win out over hopes of a swift transition within the state, according to Suravee Nayak, an energy policy researcher based in New Delhi.

“We see the energy transition everywhere in [the Odisha government’s] thinking about future development,” she says. “Until and unless renewables vigorously contribute to energy production in the country . . . we cannot really say that coal is going to be unimportant.”

Data visualisation by Steven Bernard