The numbers seemed too implausible and counterintuitive, especially for an 8-billion strong species dominating almost every corner of the planet today.

How could such a tiny cluster of humans have managed to sustain the species over such a long time span?

Advertisement

For more than three years, Pan and evolutionary genomics researcher Li Haipeng at the Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health ran repeated studies to test the credibility of these figures, but accumulating evidence increasingly convinced them that the results might be tenable.

Published in Science on Friday, their research findings have now captured global attention.

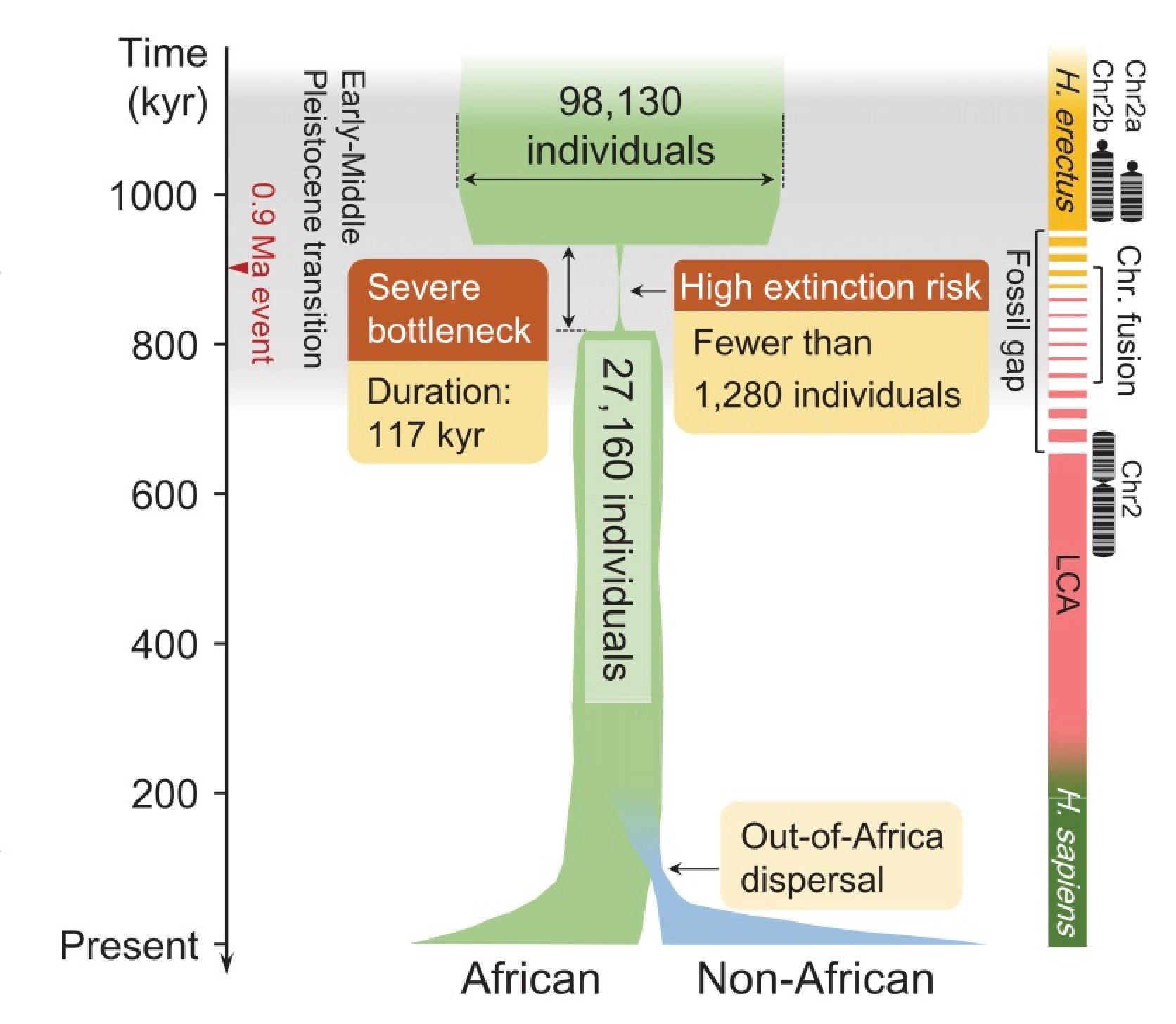

According to the paper, between 930,000 and 813,000 years ago, ancestors of a species of modern humans suffered a period known as a “bottleneck” – a prolonged, severe crisis of numbers following the loss of about 99 per cent of the population.

Once that crisis was over, however, the population rebounded.

A bottleneck is a common evolutionary phenomenon. Disease, natural disasters and climate change can all drive species to the edge of extinction, forcing them to adapt or die.

Advertisement

“The size of populations is a crucial parameter for our understanding of human evolution,” Dr Jin Xin, deputy director at China’s BGI Research Institute, who was not involved in the study, told the Post.

“It directly impacts the diversity of the human genetic heritage and the history of evolutionary migrations. This body of knowledge forms the foundation for studying various complex diseases. ”

Advertisement

Understanding of ancient humans had been largely limited to the last 100,000 years, primarily focusing on the “Out of Africa” migration history.

However, the bottleneck event observed by the Chinese researchers happened hundreds of thousands of years before this migration. “This really extends the time frame of understanding population history significantly,” Jin said.

Pan, who co-authored the paper, described their findings as “a milestone”.

Advertisement

“Current anthropology research regarding this period of time mainly relies on scattered fossil evidence or astronomical and geographical data, but we engage in genuine statistical analysis of how human populations had changed in size,” said Pan, who is affiliated to Shanghai’s East China Normal University.

This “ancient human census” was made possible by a novel method developed by the authors.

The system, dubbed FitCoal (short for “Fast Infinitesimal Time Coalescent”), enabled the researchers to determine demographic inferences by using contemporary human genomic sequences in a more accurate and efficient way, Pan said.

Advertisement

Every human genome contains over 3 billion genetic bases or “letters” of DNA, each inherited from our ancestors over hundreds of thousands of years – creating a vast record of our evolutionary history.

Meanwhile, powerful DNA sequencing technology today has facilitated the decoding process significantly.

Chinese relics point to unbroken cultural links that began a million years ago

Chinese relics point to unbroken cultural links that began a million years ago

The Chinese study compared the genomes of about 3,000 people from 50 populations around the world from two independent data sets, the Thousand Genomes Project and the Human Genome Diversity Project.

These findings also throw new light on the origins of modern humans.

The supposed bottleneck lay right in the middle of the period when the first human species is thought to have appeared. It seems to have contributed to a “speciation” or new species creation event – where two ancestral chromosomes may have converged to form what is currently known as chromosome 2 in modern humans.

FitCoal could be applied as a fundamental research tool to virtually all genetically driven life forms such as plants, animals, bacteria and viruses, the researchers said.

“It has the potential to be utilised beyond academic research and bring tangible benefits,” Pan told the Post.

One possible scenario would be understanding the development of cancer, as all tumour cells can be “conceptualised” as populations for calculation and assessment, she said.

The ancient genome project represents a decade-long effort by Pan and Li, who co-led the study sparked by an initial desire to create a better method for reconstructing past population sizes. Two scientists based in Italy and another in the United States also made significant contributions to the findings.

After sailing through multiple setbacks, the team finally had their first remarkable discovery – evidence of the bottleneck about a million years ago.

‘Great find’: Peruvian, Japanese archaeologists find pre-Incan relics in Peru

‘Great find’: Peruvian, Japanese archaeologists find pre-Incan relics in Peru

Last year, the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine was awarded to Swedish evolutionary geneticist Svante Pääbo, who extracted and sequenced ancient DNA from Neanderthal fossils dating back 38,000 to 45,000 years. Along with the pioneering research into the extinct relatives of present-day humans or Homo sapiens, he also discovered a previously unknown early hominin, the Denisova.

“We were the first team who could ‘see’ so far in the population history of human beings and the result was so hard to believe,” Pan said.

They deployed several ways to verify this phenomenon.

For example, sequencing based on both the Thousand Genomes and Human Genome Diversity projects showed the estimated population size to be remarkably consistent.

Further validation of a bottleneck was provided by tests conducted on samples from the southern African population – thought to possess the maximum genetic diversity.

In 2021, the team submitted the first version of their paper on the preprint platform bioRxiv and offered FitCoal for open download.

“Two archaeologists were excited about our work,” Pan said. “There was a fossil gap in archaeology that coincided with the period when we observed the extreme life loss, so they considered our discovery a fascinating and credible one. Thus, we began to collaborate and they helped supplement evidence from an archaeological perspective.”

Fossil records of ancient humans in Africa remain relatively scarce in Africa in the period between 950,000 and 650,000 years ago.

The paper suggested that climatic reasons might have accounted for this near-extinction, such as glaciation events around this time, with the colder and drier weather making hunting for food more difficult. It also proposes that the use of fire may have played a role in the population recovery after the bottleneck.

However, some scientists argue that the latest research is just one of many possible theories to construct evolutionary history.

Nick Ashton, an archaeologist at the British Museum, said FitCoal certainly seemed to have the potential to reveal more about human lineage, but the interpretation offered in the paper also needed to be tested against current archaeological and human fossil evidence.

About a million years ago, human ancestors had evolved to be tall and big-brained in Africa. Afterwards, some of those early humans spread out to Europe and Asia, evolving into Neanderthals and the Denisovans, while our current lineage – the Homo sapiens – continued to evolve into modern humans in Africa.

“But due to the uncertainty of the date of the last common ancestor – before or after the bottleneck – it’s not clear whether this affected our own lineage as well as Neanderthals and Denisovans,” Ashton told the Post in an email response.

Professor Chris Stringer, an expert in human evolution at The Natural History Museum London, is also in favour of wider application of the FitCoal model.

“It would be good to see the new model applied to other genomic data such as for Neanderthals and Denisovans,” Stringer told the Post.

In a “Perspectives” article published in the same Science issue, Ashton and Stringer said that fossil records dating to the inferred bottleneck period suggested humans were widespread inside and outside of Africa.

Therefore, the event may have had limited or short-lived effects on the overall human population.

“These findings are just the start,” Li said. “Future goals with this knowledge aim to paint a more complete picture of human evolution during the Early to Middle Pleistocene transition period, which will in turn continue to unravel the mystery that is early human ancestry and evolution.”

Advertisement