The region, stretching from the Pacific to the Indian Oceans, represents a geostrategic zone of mounting importance. But even as the US tries to make headway with Pacific island nations, smaller Indian Ocean nations remain largely absent from America’s regional strategy.

During a US House Foreign Affairs hearing in April on China’s influence in the Indian Ocean region, experts testified that Washington’s vision of the Indo-Pacific downplays the significance of the region in its great power competition with China.

Most nations of the Indian Ocean are excluded from policy discussions about the Indo-Pacific, witnesses said, and when policymakers discuss the region, they often refer to the Pacific and areas around the South China Sea or East China Sea.

Washington “implicitly” wants to ensure the Indian Ocean does not assume greater priority than the increasingly interconnected Pacific, Arctic and Atlantic theatres, Nilanthi Samaranayake of CNA, a US-based non-profit group, told the panel.

Nilanthi Samaranayake of CNA testifying before a US House foreign affairs subcommittee in Washington last month. Photo: Handout

“The Indian Ocean needs to remain a lesser priority for the US as it allocates limited resources globally in a new era of strategic competition,” she said.

Samaranayake believed the US understood the Indo-Pacific from a Pacific lens while appearing to “outsource” its Indian Ocean policy involving small nations to regional powers like India.

Indeed, there was but one significant mention of the Indian Ocean region in the White House’s 19-page Indo-Pacific Strategy document published in February last year.

Without spelling out US strategy in the Indian Ocean, the document identified India as a “like-minded partner in South Asia, and the Indian Ocean, active in and connected to Southeast Asia”.

Experts bemoan the slim treatment. More than 2.7 billion people live on the Indian Ocean’s coastlines, accounting for 12 per cent of the world’s GDP. And the six island nations found there – Sri Lanka, the Seychelles, Maldives, Mauritius, Madagascar and the Comoros – have exclusive access to their surrounding waters.

A map of the Indian Ocean showing the Maldives, Seychelles, Comoros and Mauritius, as well as Madagascar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, India, China and Indonesia. Also pictured are the Strait of Malacca, Bab al-Mandeb and the Strait of Hormuz. Photo: SCMP/Datawrapper

What is more, the region provides an economic lifeline for much of the world, with three geographical choke points critical to global trade.

The Strait of Malacca is the main shipping link between the Middle East, East Asia and Europe. In 2016, some 16 million barrels of crude oil and 3.2 million barrels of liquefied natural gas were transported daily through the strait, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

There is also the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow channel between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman through which about a third of the world’s seaborne crude oil passes.

Another key strait is the one known as Bab al-Mandeb, along a vital maritime route between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, connecting the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea to the Red Sea and Suez Canal.

[embedded content]

The Indian Ocean is China’s “primary theatre of transit” for engaging with Africa and the Middle East and represents its main trading route to Europe, according to Darshana Baruah of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Over 40 per cent of China’s crude oil comes from Middle Eastern countries.

Baruah said China increasingly perceived the Indian and American presence in the Strait of Malacca as a threat to its energy routes and undersea communication cables.

“If there is any attempt at establishing deterrence for [the] Taiwan Strait crisis on the maritime domain, I think that would come around the Strait of Malacca,” she said.

Beijing considers Taiwan a renegade province that is to be brought under its control, by force if necessary.

Baruah said the tiny Comoros would be “a critical waterway and a primary route for transit should the Suez Canal and the Bab al-Mandeb be inaccessible”.

Despite being a relatively new player in the region, Beijing has outpaced the US in making diplomatic inroads, she added.

Unlike the US, Britain, India or France, China is the only nation to operate an embassy on each of the Indian Ocean’s six island nations, Baruah said.

“China is perhaps one of the few nations, if not [the] only, to send high-level delegations and visits to the islands of [the] Comoros, a strategically located nation but widely neglected by the international community,” she said.

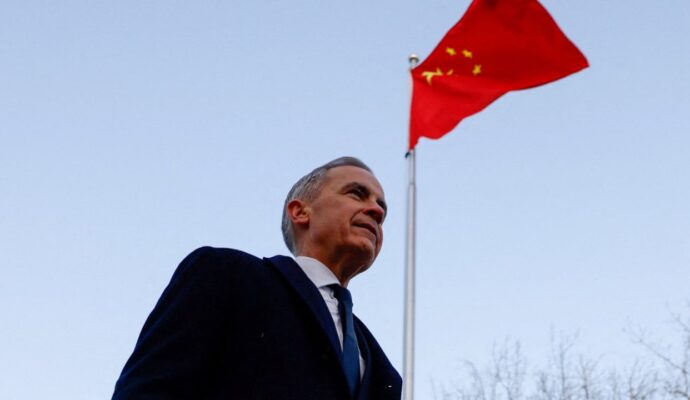

Chinese President Xi Jinping welcoming Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan in Beijing last November. Photo: Xinhua

Mayotte, a French territory, recently began returning boats full of illegal immigrants from the neighbouring Comoros. In retaliation, the Comoros closed it ports, refusing to accept them back.

In contrast, in 2018, China forgave Comorian debt and pledged further investments. In 2021, the Comoros became the 41st African country to join the Belt and Road Initiative, a China-centred trading network.

And in December, Chinese President Xi Jinping met his Comorian counterpart in Riyadh, vowing to support the “Comoros in playing a greater role in international and regional affairs”.

Fishermen carry a timber boat on Anjouan island in the Comoros last month. Photo: AFP

In 2017, then Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi visited the Seychelles, Madagascar and Tanzania. In the Seychelles, Wang signed an agreement to boost bilateral development cooperation.

Over the past decades, trade between China and the Seychelles has grown steadily, rising by over 7 per cent in 2019. Since 2015, China has been Madagascar’s largest trading partner.

But the US and its Indo-Pacific partners like India regard Chinese loans as a “debt trap” to further its “string-of-pearls” strategy of establishing Chinese ports along the Indian Ocean coastline.

US President Joe Biden meeting virtually with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Washington in April last year, with Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh (centre) and Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar. Photo: AP

India has long speculated about China setting up a military base in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota and Pakistan’s Gwadar ports, both built with Chinese money. Sri Lanka, which defaulted on its debts last year, owes about US$7 billion to China.

After the deadly 2020 clashes between Indian and Chinese troops over their contested Himalayan border, India raised apprehension about a proposed Chinese satellite ground receiving station in Sri Lanka and Chinese military facilities on Myanmar’s Coco Islands.

Though none of that speculation has been confirmed, China did establish its first and only overseas military base in Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa, in 2017. Eight countries, including the US, France and Japan, have naval bases in the port state. There have been reports of a Chinese commercial port in Tanzania.

As India, backed by the US, and China compete to expand their security perches in the region, smaller countries like Maldives, Mauritius and the Seychelles are grappling with a geopolitical tug of war. In 2015, Mauritius allowed India to build a military base on its island of Agalega, which neighbours the American base on Diego Garcia.

India’s push for a similar deal with the Seychelles failed, while China helped the island nation build a new parliament and supreme court. China also donated two light aircraft and two naval vessels to the Seychelles.

In addition, India and others have voiced concerns about elevated Chinese naval activity in the region. India’s naval chief Admiral R Hari Kumar said two weeks ago that India was “closely watching” the situation.

“At any point of time, there are three to six Chinese warships in the Indian Ocean region,” Kumar said.

In 2014, China sent its first submarine to the region to participate in anti-piracy initiatives. And since 2018, Beijing has been sending its navy on such missions in the Gulf of Aden between Yemen and Djibouti, sailing across the Indian Ocean.

Darshana Baruah of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace testifying at Congress last month. Photo: Handout

Beijing’s presence affords an “opportunity and space” for it to make port calls in Indian Ocean nations like Sri Lanka and “additional capacity and influence during crises, said Baruah of Carnegie. She noted China’s prompt response to a water crisis in the Maldives in 2014 “despite being a non-Indian Ocean nation”.

The contest to ramp up naval presence in the region brought an exceptionally busy March: Australia, Canada, the US, France, India, Japan and Britain conducted high-level training exercises in the Bay of Bengal on March 13 and 14.

Later that week, Russia, China and Iran carried out four days of joint naval manoeuvres in the Gulf of Oman.

To check China’s ambitions, experts said, the US needs to directly engage with smaller nations in the Indian Ocean without relying excessively on India.

Samaranayake of CNA warned that approaching the Indian Ocean merely through India undermined Washington’s direct involvement in the region.

It ignored how India’s smaller neighbours were “already suspicious of US-India relations in the context of China and in the backdrop of India’s dominance in the region”.

In calling for a US national strategy focused on the Indian Ocean region, Samaranayake said Washington must consider these smaller countries’ development goals.

Specifically, they were “increasingly facing pressure due to major power rivalry, like managing their economic activities, while navigating sanctions on Russia and the dynamic of strategic competition with China”.