Deng’s successors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao have followed his doctrine by expanding the role of market forces while keeping a low profile for China on the international stage.

Jiang came up with his own phrase to summarise his style of governance, men sheng fa da cai (keeping quiet will help you make a fortune), while Hu’s is shorter – bu zhe teng (this has many meanings but usually, don’t flip-flop or don’t dither).

Their pragmatism has ensured China’s rise to become the world’s second-largest economy in merely 30 years.

Over the past decade, however, ultra-leftist national sentiment has made a comeback with a vengeance, threatening to derail China’s economic development.

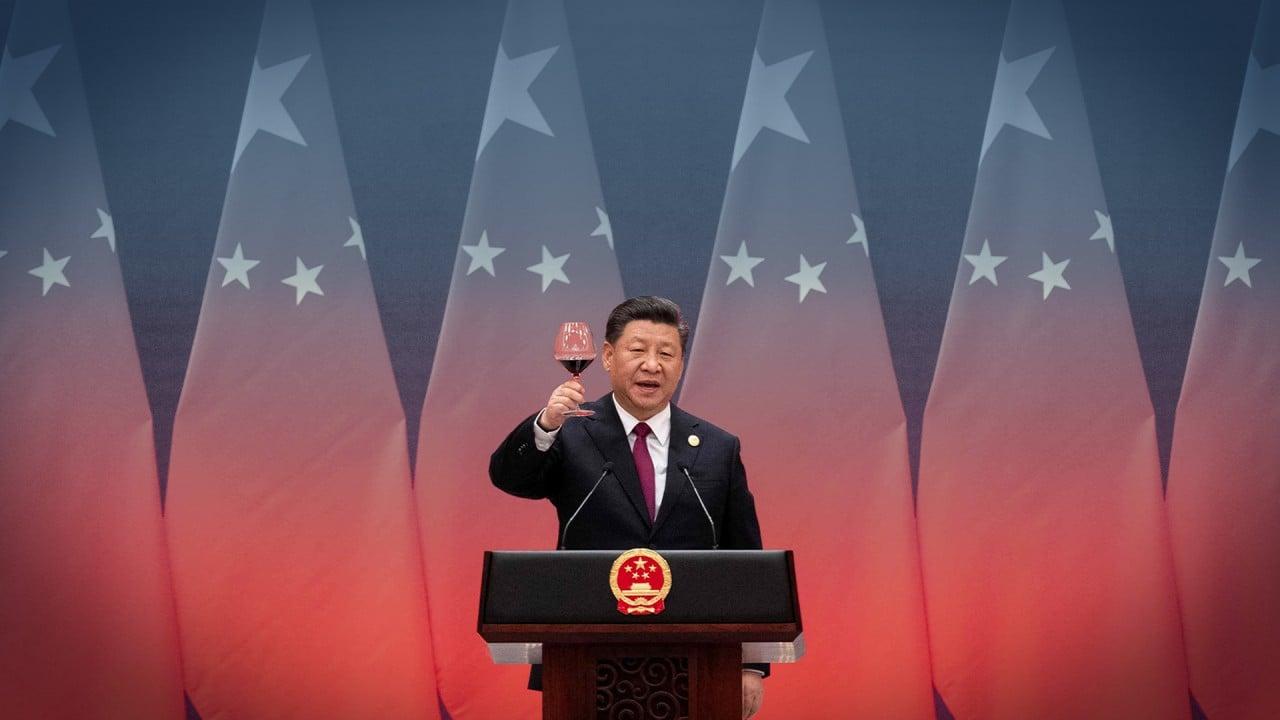

Since coming to power in late 2012, Xi Jinping has consolidated power in his hands and strengthened the party’s control over all levels of society with the sharp claim that “east, west, south, north and centre, the party leads everything”.

Abroad, the party jettisoned Deng’s dictum of “hiding one’s strength and biding one’s time”, openly clashing with the United States and its Western allies across ideological lines and over values.

To make it worse, ultra-leftists have taken advantage of China’s confrontation with the US and the crackdown on the private sector to push their agenda under the guise of patriotism and allegiance to Communist ideals. Their influence has now largely moulded China’s domestic policies and stance on external relations.

To put it bluntly, if the ultra-leftist sentiment remains unchecked, China’s development risks being derailed, and China’s goal of national rejuvenation – Xi’s ambition to turn the country into a dominant world power by the middle of the century – will remain just a dream.

The opportunity has come for China’s top leaders to take serious steps to curb the ultra-nationalistic tendencies and get back on the track of reform and development.

China’s legislature, the National People’s Congress, opened its annual session yesterday, with the top agenda item to elect a new government, including the president, premier and other top officials. It will largely be a ceremonial affair because the leadership changes at the party’s 20th Congress last October have already determined the key positions.

Xi is set to secure the presidency for another five years while his closest ally, Li Qiang, will become premier, with the rest of the new cabinet full of Xi’s supporters.

The importance of this new cabinet should not be underestimated. The party might use the formation of the new government to signal a conciliatory approach at home and abroad, as it needs a more stable domestic and international environment to focus on reviving the economy.

At home, Li is expected to unveil pro-market measures in the coming months to boost the confidence of investors and consumers.

Abroad, China is expected to soften its hawkish stance towards the West. China has released a position paper calling for a political settlement of the Ukraine crisis on the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion. Amid international concerns about Beijing’s growing ties with Moscow, China is presenting itself as a peace broker.

French President Emmanuel Macron is expected to visit China early next month while Fu Cong, China’s ambassador to the European Union, has frequently met EU officials to explore the possibility of reviving the EU-China investment treaty, which was frozen because of the tit-for-tat sanctions over Xinjiang.

China and the US may have exchanged angry words over the “spy” balloon incident but there are suggestions that both Washington and Beijing want the incident to blow over, no pun intended.

But signalling a conciliatory approach is not enough. China’s leaders face growing scepticism at home and abroad after their policy blunders and three years of zero-Covid, during which confidence in the rule of law was seriously compromised as officials locked people inside their homes or sent mildly infected people to quarantine centres for weeks in the name of pandemic control.

Underneath all those wanton acts and disregard for the rule of law are ultra-leftist tendencies running amok.

It is high time to revisit Deng’s warning and return to the practices of bu zheng lun and bu zhe teng.

Wang Xiangwei is a former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He now teaches journalism at Hong Kong Baptist University