Internationally, strengthening the social security net is a usual part of efforts to tackle inequality. But according to the International Monetary Fund, China’s spending to protect workers and the vulnerable in 2018 trailed behind that of other large emerging market economies.

This is an inadequacy that was likely to be exposed – if not already from published statistics – as the Covid-19 wave spreads.

That is unfortunate. But one of the beliefs that underpins China’s current uncommon prosperity, which is that companies, not households, are the best transmission vehicles for fiscal policy, is deep-seated in Beijing, and so has implications not just for public health, but also the economy.

Unlike in many other countries, pandemic payouts to support households have been insignificant in China. In the initial Covid-19 breakout of early 2020, China didn’t need to implement the nationwide lockdowns deemed necessary elsewhere, so the lack of significant income support for households wasn’t especially damaging. But as China’s Covid-19 crisis dragged on, it became more obvious that households are the biggest economic casualties.

By the end of 2022, industrial production was up by almost 25 per cent from December 2019. But the volume of retail sales had risen only by around 1 per cent.

The weakness in the household sector isn’t just reflected in spending. Income growth has also dropped. In the five years before 2020, annual urban household income growth averaged 8 per cent. In the three years since, that has fallen to just 5 per cent; last year, it was less than 4 per cent.

With consumption growing even less than incomes, savings have expanded. And there is now hope that, as in the United States and other richer economies, a running down of these savings will fuel a strong post-Covid rebound in China.

Such hopes aren’t completely unjustified. With consumption having been so depressed, and the government wanting to turn the economy around, household spending should grow. Data for December already showed a stabilisation of the big deflationary shift of the last five years of household savings into longer-term time deposits.

Still, observers have been hoping for years that household savings in China would start to fall, and that is yet to happen. With the extra bump in savings during the pandemic, bottom-up data suggests that the household savings ratio at the end of 2022 rose above 40 per cent, which is high even by China’s world-beating standards.

The precautionary motive – putting money aside for a rainy day – is commonly used to explain why savings are so high. That makes sense given the holes in the social security net.

There is a risk the Covid-19 crisis has intensified the motivation to save as households conclude that at least some of the negative income shock of 2020-22 proves permanent. The central bank’s fourth quarter survey last year showed income confidence falling to a low.

At their December meeting, officials pledged to “increase the income of urban and rural residents through multiple channels”. That sounds promising, and so perhaps a departure from the traditional way of doing things is in the works, with some real largesse for households in the offing.

But so far, there hasn’t been any follow-up. Without it, China is at risk of real economic scarring from the Covid-19 crisis.

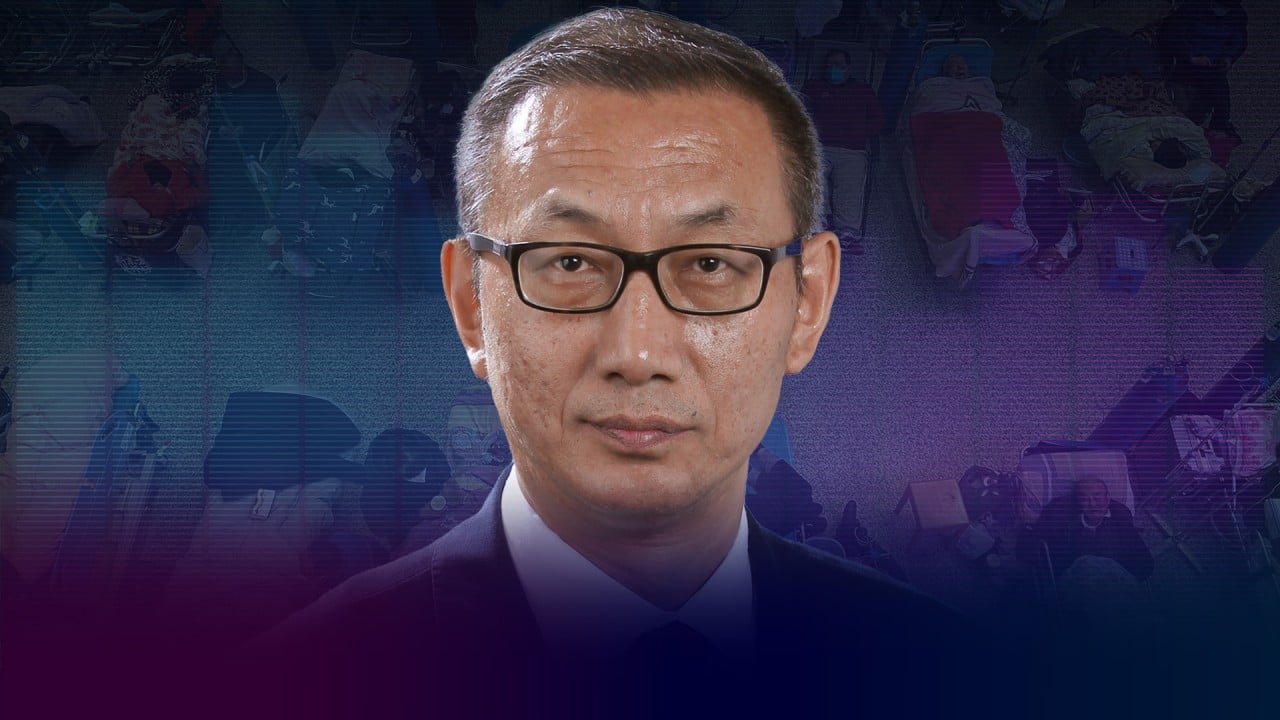

Paul Cavey is a China-focused Asia economist with 25 years’ experience covering macro and markets in the region. He established East Asia Econ, a macroeconomic consultancy, in 2022